RECAP: State of Democratic Freedom in Africa

Narratives around the state of democracy in Africa tend to swing between exuberant optimism and gloomy pessimism. Recent electoral outcomes across the continent, however, reveal a more nuanced reality that defies easy characterization. In what some analysts have seen as part of a global “anti-incumbent election wave,” 2024 saw opposition parties achieve remarkable victories across several African nations with relatively robust democratic institutions, suggesting a vibrant and resilient demand for democracy. For example, the Botswana Democratic Party lost its parliamentary majority after 58 years of uninterrupted rule. South Africa’s African National Congress fell below majority status for the first time since the end of apartheid in 1994, forcing it into a coalition government. Similarly, opposition victories in Senegal, Ghana, Somaliland and Mauritius all signaled a broader trend of both electoral accountability and dissatisfaction with the status quo.

These outcomes reflect several connected factors: widespread economic discontent exacerbated by slow post-pandemic recoveries, as well as by rising global inflation related to ongoing wars in Europe and the Middle East; local perceptions of corruption and governance failures; demographic shifts, with younger voters less tied to liberation narratives and more motivated by their own diminished prospects; and—perhaps most significantly—the presence of independent judiciaries and electoral commissions, free media, and active civil societies that have helped translate public discontent into peaceful political action.

But the enthusiasm around these peaceful transitions is tempered by several less desirable electoral outcomes, which suggest that in places where democratic traditions have been slow to take root—such as Mozambique, Chad, and Comoros—it remains difficult to challenge embedded incumbents and overcome the capture of state institutions. For example, the deeply entrenched Mozambique Liberation Front (FRELIMO) was able to undermine what was hoped to be a competitive election, instead extending its nearly 50-year hold on power in a process marred by widespread allegations of fraud that sparked violent unrest. Similarly, violence erupted in the lead up to Chad’s presidential vote, with the leading opposition candidate being killed in a standoff with federal forces earlier in the year; President Mahamat Déby formally succeeded his deceased father as president after overseeing the ratification of a new constitution that allowed him to run while serving as the transitional head of state.

With another 10 presidential contests scheduled to take place in 2025, this year is already shaping up to be significant for African politics. The first, which took place in Gabon on April 12, offers a complicated counter-narrative to both the optimistic and pessimistic narratives that predominate—perhaps indicating what might lie ahead for the continent’s upcoming elections. As with Chad’s election last year, Gabon saw a junta leader take power, with General Brice Oligui Nguema securing a landslide 90.4 percent of the vote after altering the country’s transitional constitution to allow himself to run. While many Gabonese and outsiders might argue that having no candidate on the ballot with the last name “Bong” for the first time in more than 50 years is an accomplishment worth celebrating—as is the calm atmosphere of the campaign process—it is hard to argue that Gabon’s election represents a true transition to democratic rule. While on paper the outcome has fulfilled the promise of a transition, it has perhaps more accurately consolidated military power under a democratic veneer. If anything, Gabon’s election demonstrates how seemingly democratic processes can simultaneously reinforce authoritarian tendencies, highlighting the complicated nature of political transitions in Africa.

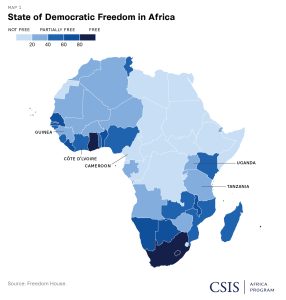

In this light, some of the most consequential African elections of 2025 will occur in countries where incumbents cling to power through constitutional manipulations and institutional capture. In others, the electoral environment is sure to be more contested. Will we see more of the kind of middle-ground “managed democracy”—hewing closely enough to democratic procedures but without the substantive conditions for genuine competition or accountability—or might true change be on the horizon? There are several African elections worth watching in late 2025 to help make this determination: Cameroon, Tanzania, Côte d’Ivoire, and Guinea. In January 2026, Uganda is set to hold presidential elections, after the country has been under the rule of President Yoweri Museveni for nearly four decades since 1986. Now 80 years old, Museveni’s continued hold on power raises growing questions about succession and the future of governance in Uganda. Meanwhile, civil society organizations, independent media outlets, and human rights defenders face an increasingly repressive environment.