The Global Fight Against Poverty: A Decade into the SDGs and how far we have come

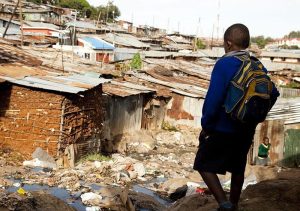

On a humid afternoon in Nairobi’s Kibera settlement, 12-year-old Amina sits cross-legged in a dimly lit classroom, carefully sounding out the words in her English textbook. Just a decade ago, the odds were stacked against her. Girls in her neighborhood often dropped out before finishing primary school, trapped in a cycle of early marriage and poverty. But Amina, part of a generation shaped by global investments in education, represents a different future. “I want to be a teacher,” she says, her smile betraying both pride and defiance.

Amina’s dream is part of a much larger story, one that began in 2015, when nearly every country in the world signed onto the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These 17 targets were more than just policy jargon: they promised to end extreme poverty, protect the planet, and ensure prosperity for all by 2030.

Eight years on, how close are we to keeping that promise?

Poverty’s Decline and Its Stubborn Grip: Back in 2015, the world celebrated a historic milestone: for the first time, fewer than 10% of the global population lived in extreme poverty. By 2023 that figure stood at 8.5%, as equal to 659 million people down from 1.9 billion in 1990. In East Asia, entire generations were lifted out of destitution. In the 1990s, poverty gripped more than 60% of people across the region. Today, the figure hovers below 5%.

But in Sub-Saharan Africa, the story is grimmer. In a village outside Kano, Nigeria, 34-year-old Musa Ibrahim recounts how his family lost everything during the pandemic. “Before COVID, I worked in the city, sending money home. Then the lockdown came, and I lost my job. My children stopped going to school because we could not pay.”

Musa’s struggle echoes across the continent, where conflict, climate shocks, and rapid population growth have left millions vulnerable. In 2020, COVID-19 reversed years of hard-won progress, pushing poverty rates up for the first time in decades. While recovery is underway, the setback exposed how fragile global gains remain.

As concerning the Health Revolutions, from HIV to maternal care, not all is bleak. If poverty reduction has stumbled, global health has seen near-miraculous advances. In rural Malawi, 28-year-old Grace cradles her newborn daughter with relief. Two decades ago, childbirth here was perilous; maternal deaths were common, and healthcare scarce. “My mother lost two babies before me,” Grace says softly. “Now, we have nurses, medicines, and help.”

Her experience reflects a global trend. Since 2000, maternal deaths have dropped by more than one-third. The under-five mortality rate has fallen nearly 60%, meaning millions more children now live past their fifth birthdays. Diseases that once seemed unbeatable are being pushed back: malaria deaths have dropped nearly 28% since 2004, while AIDS-related deaths in Africa have fallen by 40% since 2010.

The spread of life-saving antiretroviral treatment transformed HIV from a death sentence into a chronic, manageable condition. In 2017, HIV/AIDS was no longer Africa’s leading killer.

With Girls in classrooms and women in power, perhaps the most dramatic transformation lies in education and gender equality. In Bangladesh, 19-year-old Taslima beams as she scrolls through her university acceptance email on a borrowed smartphone. Her mother, who never finished primary school, wipes away tears of pride. “I wanted her life to be different from mine,” she says.

Globally, more than 180 million additional girls are in classrooms today compared to 1995. Female enrollment in universities has tripled, reaching 115 million by 2018. And for the first time in history, every parliament in the world has at least one woman in office. Women’s representation in politics has doubled since 2000, from 11.7% to over 26%.

Still, barriers remain. Gender-based violence, wage inequality, and cultural norms continue to restrict women’s opportunities, especially in fragile states. But the gains are undeniable: the sight of girls like Amina, Taslima, and millions of others in classrooms signals a generational shift.

Besides the digital divide, energy divide and beyond education, another revolution is reshaping an upwardly progressive opportunity tagged – connectivity. In 2000, only 7% of the world’s population had internet access. Today, nearly two-thirds or 5.18 billion people are constantly online. From rural communities in Kenya to remote villages in India, smartphones are not just gadgets, they are lifelines to banking, education, healthcare, entertainment, connectivity, SMEs, e-commerce, self-aggrandizement, national orientation/information, bills payment, sex marketing, etc.

Electricity access tells a similar story. In 2000, more than one in five people lived in darkness. By 2021, over 91% of the world had access to power. For families like Musa’s, the simple act of turning on a light bulb means children can study after sunset and businesses can thrive.

Nutrition, a silent but steady progress: behind these notion, daily victories on this social needs are silent wins. Childhood stunting, a measure of chronic malnutrition, has dropped from 33% in 2000 to 22.3% in 2022 and counting. That means tens of millions of children will grow up healthier, better, able to learn and more prepared to escape the cycle of poverty.

A Fragile Future connote numbers that paint a complex picture, with astonishing progress on health, education, SMEs, connectivity, etc., but stubborn challenges in poverty reduction. The SDGs promised to eradicate extreme poverty by 2030. With just five years left, that target seems increasingly out of reach.

Still, experts argue that setbacks do not erase progress. “We are better off than we were two decades ago,” says Dr. Anjali Mehta, a development economist. “The world has shown that when governments, communities, and individuals work together, change is possible. But we cannot afford complacency.”

For Amina in Nairobi, Grace in Malawi and Taslima in Bangladesh, the SDGs are not abstract targets but lived realities. Their stories of opportunity gained, health restored and barriers broken, prove that global goals can touch individual’s life.

The fight against poverty is still far from over. But as humanity edges closer to 2030, one truth endures a struggling-stance that ‘progress is possible’ even in the face of crisis.