Fresh Hope for Peace in Battle-Scarred Congo Sparks as New Peace Draft Ensues

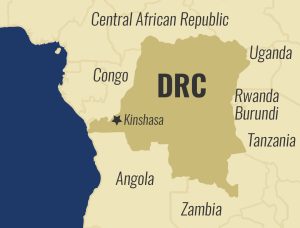

With Kinshasa and Doha on the role-play, efforts to end decades of conflict in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) have gained fresh momentum as mediators confirmed the circulation of a draft peace agreement between the Congolese government and the M23 rebel movement. The draft, shared in Doha under Qatari and U.S. mediation, is seen as a crucial step toward halting a war that has devastated communities, strained regional relations, and disrupted global mineral supply chains.

A Qatari official involved in the talks described the document as “a preparation and sharing of a draft peace agreement with both parties,” adding that negotiations remain ongoing despite missing the August 18 deadline for a finalized deal. The draft builds upon the July 19 Doha Declaration of Principles, which laid out commitments to restore state authority in rebel-held areas, release prisoners, and allow the safe return of millions of displaced civilians.

Regional Actors and Geopolitics: The peace effort unfolds against a complex regional backdrop. Rwanda, long accused by Kinshasa and international observers of backing the M23 rebellion, signed a separate U.S.-brokered peace accord with the DRC in June. That agreement, dubbed the Washington Accord to obliged Rwanda to withdraw its forces and curtail support for armed groups in exchange for enhanced economic integration and joint border security. However, the M23 was not party to that deal, necessitating parallel negotiations in Doha.

The involvement of both Qatar and the United States underscores the global dimension of the crisis. Washington views eastern Congo’s instability as a threat to regional security and global supply chains, particularly given the area’s wealth in coltan, cobalt, and other minerals critical to electronics and electric vehicles. Analysts argue that a durable settlement must balance political concessions with economic frameworks that address resource governance, revenue sharing, and the illicit mining networks that fuel armed groups.

Humanitarian Conditions: The stakes could not be higher for civilians. The latest resurgence of fighting has displaced more than seven million people, according to humanitarian agencies, many of them sheltering in overcrowded camps around Goma and Bukavu. Aid groups warn of spiraling malnutrition, disease outbreaks, and gender-based violence as communities remain cut off from farmland and markets.

“The humanitarian toll is staggering,” said a Kinshasa-based relief coordinator. “Without a peace settlement that addresses security, justice, and livelihoods, displacement will remain a permanent condition.”

Path Ahead: While the draft agreement offers hope, challenges loom. Previous ceasefires have collapsed under mutual distrust and lack of enforcement. The Doha process currently lacks a robust verification mechanism, raising fears that both sides could backslide. Moreover, the political calculus in Kinshasa ahead of upcoming elections, and the M23’s entrenched control over lucrative mining zones, could complicate implementation.

Still, diplomats see the convergence of multiple peace tracks as a rare window of opportunity. If harmonized, the Washington Accord with Rwanda and the Doha draft with the M23 could lay the foundation for regional stabilization and economic recovery.

For the people of eastern Congo, battered by years of war, the draft represents more than words on paper. It is a fragile promise that peace, which was long elusive, may finally be within reach.