Kenya’s Debt Dilemma: Why Nairobi is Turning to China’s Yuan to Ease Dollar Pressures

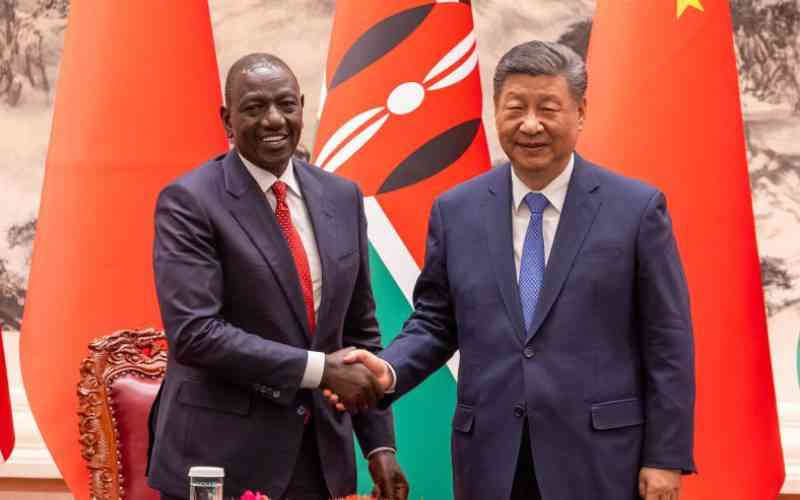

In the bustling corridors of Kenya’s National Treasury, a quiet but high-stakes negotiation is underway. Nairobi is in talks with Beijing to convert part of its dollar-denominated loans into Chinese yuan and to extend repayment terms. This is a move that could reshape not only Kenya’s debt management but also its geopolitical positioning.

At the heart of this maneuver lies a pressing reality: Kenya spends nearly $1 billion annually servicing debt to China, its largest bilateral creditor. With an external debt burden of $40.5 billion as of March, which owed to the World Bank, Eurobond investors and China, the strain on the country’s finances is becoming increasingly unsustainable.

Dollar-denominated loans have long been the backbone of Kenya’s borrowing strategy, but the rising strength of the U.S. dollar against the Kenyan shilling has magnified repayment costs. Every fluctuation in exchange rates translates into billions more in local currency terms, squeezing public finances and reducing fiscal space for development.

By shifting part of its repayment obligations into yuan, Nairobi hopes to reduce these pressures. Officials suggest that such a conversion could cut interest costs by half while offering longer repayment periods. For Kenya, this would free up resources to fund the infrastructure, health and education sectors that have been starved as debt repayments consume more than half of government revenue.

“The dollar has been a heavy burden,” one Treasury insider explained. “Settling part of our obligations in yuan aligns with our trade flows with China and reduces exposure to dollar volatility.”

For ordinary Kenyans, the country’s ballooning debt is not just an abstract economic issue—it is felt in everyday life. Rising taxation, higher fuel prices, and cuts in government spending have become common as Nairobi struggles to plug budget gaps.

Street vendors in Nairobi complain of fewer customers as purchasing power shrinks. Teachers and doctors protest delayed salaries. Young graduates, already facing unemployment rates hovering above 30 percent, worry about a future where public resources are tied up in debt repayment rather than job creation.

“Every month it feels like the government is working for the lenders, not for us,” says Mercy Wanjiku, a small-business owner in Kiambu. “If paying in yuan will reduce the pressure, then why not? We just want some relief.”

Kenya’s talks with Beijing also carry significant political implications. On one hand, Washington and European capitals remain important partners, not only as creditors but also as aid and trade allies. On the other hand, China’s role as Kenya’s largest bilateral lender and the builder of flagship projects like the Standard Gauge Railway, makes Beijing an indispensable player in the country’s economic story.

A shift toward yuan-denominated debt could be seen as a deeper embrace of China at a time when global powers are vying for influence across Africa. For some policymakers, this diversification is pragmatic: if Kenya can balance its obligations and avoid overreliance on the dollar, it strengthens its sovereignty. But critics warn it could pull Nairobi further into China’s economic orbit, with risks of dependency and reduced bargaining power.

Parliamentarians have already raised questions about transparency, demanding clear terms for any renegotiated loans. Civil society groups, wary of past opaque deals, fear that restructuring could mask deeper fiscal mismanagement rather than resolve it.

Beyond the political elite, Kenyans are grappling with a sense of unease. Public trust in government financial stewardship has eroded, fueled by corruption scandals and incomplete mega-projects financed by Chinese loans. Communities along the Standard Gauge Railway complain of displacement without fair compensation. Urban residents lament deteriorating services despite rising taxes.

Against this backdrop, the yuan negotiations are being watched with both hope and suspicion. Many see the potential relief in debt servicing as a chance for government to redirect funds into pressing social needs. Others, however, worry that the deal could simply prolong the cycle of borrowing without addressing structural weaknesses in revenue collection and public spending.

Kenya’s talks with China highlight a broader global shift. As the yuan gains ground in international finance, more countries in the Global South are exploring alternatives to the dollar. In Nairobi’s stead, this is less about ideology and more about survival, finding room to breathe in a tightening fiscal vise.

Whether the negotiations succeed will have far-reaching consequences. A successful restructuring could stabilize Kenya’s finances, ease pressure on households, and restore some investor confidence. But failure or poorly negotiated terms, could deepen dependency and worsen public discontent.

For the time being, Kenya stands at a crossroads. Its decision to pivot part of its debt to yuan payments is not just a financial calculation, it is a reflection of the country’s struggle to balance its economic aspirations with the realities of global power politics, domestic discontent, and the everyday needs of its citizens.