Southern/Central Africa: Lobito Corridor, Transforming Local Connectivity into Limitless Continental Opportunities

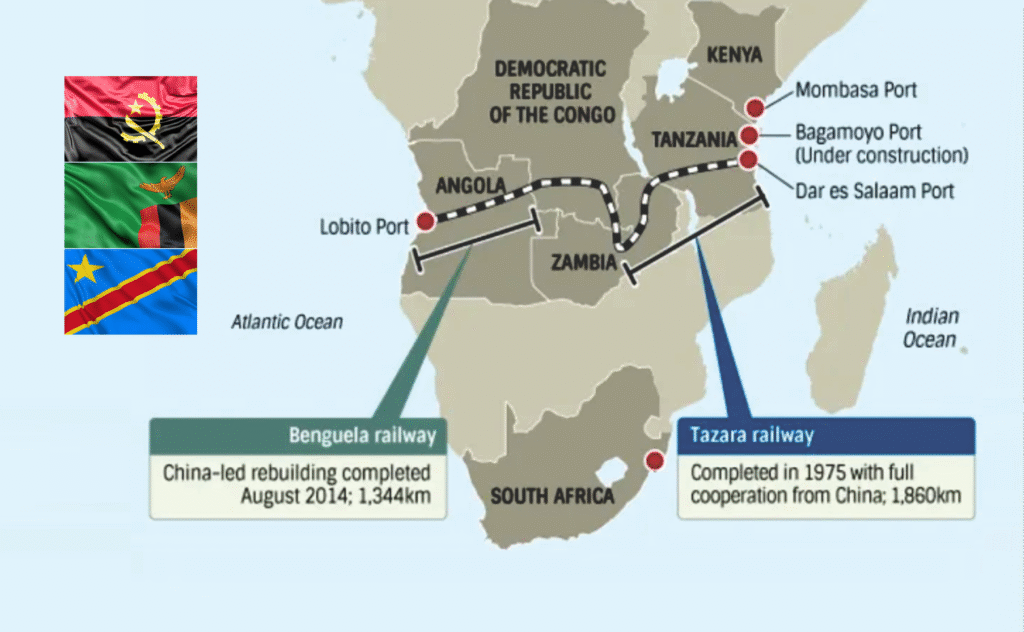

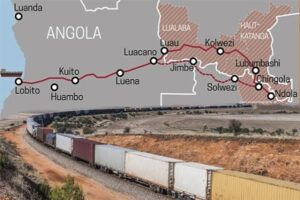

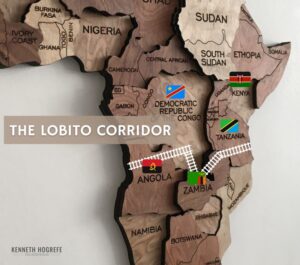

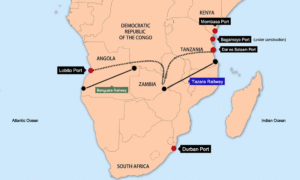

Stretching from Angola’s Atlantic shoreline through the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and into Zambia’s Copper-belt, the Lobito Corridor is emerging as one of Africa’s most consequential infrastructure projects; and potentially the continent’s first true transcontinental transport link. By shrinking freight time from more than a month to roughly one week, the corridor is reshaping mobility across central and southern Africa and quietly redefining how families, farmers, businesses and governments imagine their futures.

![]()

A corridor that travels through communities. Further than its steel tracks and paved arteries, the Lobito Corridor is generating social ripple effects that reach homes, classrooms and local markets. As for smallholder farmers, faster export routes mean higher earnings and lower post-harvest losses that can determine whether a family sends its children to school, invests in new equipment or survives a bad season.

To most women and young workers, targeted training programmes in logistics, agriculture, digital skills and renewable energy are opening pathways into sectors traditionally closed off or dominated by foreign labour. And as rural electrification and clean water projects expand along the route, everyday burdens of fetching water, studying in the dark, or travelling long distances to clinics, are slowly easing. Europe stakes big on African trade connectivity.

Under the EU’s Global Gateway strategy, more than €2 billion is being mobilized for the corridor. Europe’s investments follow a 360-degree model that blends hard infrastructure with softer, long-term development: from rehabilitating rail lines and border posts to strengthening agricultural value chains, biodiversity protection, TVET systems and small-business support.

The political stakes are significant. As global powers compete for Africa’s critical minerals and strategic influence, the EU is positioning itself as a partner focused on sustainability, governance and shared prosperity, an alternative to extractive models of the past. The corridor offers leverage, diversification of trade routes and the chance to negotiate from a stronger position in global value chains for many African governments.

In Angola, farmers from grains to tropical fruits are already benefiting from logistics hubs such as the Caála Platform, where the first export-bound avocados marked a symbolic turning point: local produce, transported through local infrastructure, reaching global markets.

Large-scale investments in TVET, supported by the EU, France, Portugal and the African Development Bank, mean thousands of young Angolans are preparing for work in logistics, renewable energy and digitalisation. Clean water and rural electrification programmes are quietly transforming the corridor’s social landscape: fewer preventable illnesses, safer childbirth, and more time for livelihoods rather than survival.

In the DRC, where mining dominates the economy, Team Europe’s investments aim to shift the sector toward responsibility and long-term value. Training programmes for miners and youth, ecological restoration projects in South-East Congo and support for civil society oversight, seek to ensure that minerals benefit communities first, before global supply chains.

Upgraded border facilities and rehabilitated rail links promise faster, safer travel. To traders who once spent weeks navigating unpredictable roads, the corridor represents not just economic opportunity but personal safety and dignity.

Zambia sees the Lobito Corridor as a chance to reinvent itself as a green industrial power. The new Chingola–Luacano rail line, part of a €4 billion multimodal plan, is set to cut export times from 35 days to a single week. Improved open-access rail rules could shift freight from road to rail, reducing both transport costs and carbon emissions.

![]()

In classrooms and technical institutes, students are being trained for future jobs in logistics, renewable energy and mining value addition. Clean-water and renewable-powered systems under NEWZA 2.0 are helping fast-growing towns keep pace with rising populations. Smallholder farmers, too, are benefiting from new legume and horticulture value chains that create rural employment beyond mining.

The Lobito Corridor is more than a construction project; it is the beginning of a new political geography in central and southern Africa. For decades, trade routes largely ran east-west under the logic of former colonial powers. The Lobito Corridor challenges that pattern, empowering Angola, the DRC and Zambia to build a shared economic identity and reduce dependence on congested routes in South Africa or Tanzania.

The memorandum of understanding signed with the EU, US, Italy, African Development Bank and Africa Finance Corporation, states a rare moment of geopolitical convergence, one that places African agency at the centre of regional integration.

Communities along the route see the corridor as an opportunity to reclaim their role as producers, innovators and custodians of the region’s future rather than as passive extraction zones.

The Lobito Corridor’s impact will depend on governance and local ownership. Strong institutions, transparent mineral value chains, safeguards for land rights, and meaningful community participation will determine whether the project becomes a model of equitable development or another resource corridor that bypasses the people it crosses.

At the moment, optimism is growing. Families are seeing new incomes. Youth are discovering viable careers. Governments are strengthening ties and building cross-border stability. And business leaders from farmers’ cooperatives to logistics firms, are preparing for a marketplace that no longer feels distant or unreachable.

The promise of the Lobito Corridor is not only that it connects the Atlantic to the Copperbelt, but that it connects opportunity to the people who have for too long watched it pass them by.