Africa’s Accountability, Transparency and Integrity Deficit in Leadership: A Failure in Shaping National Development

In the dynamic landscape of African organizations, courageous leadership remains a pressing necessity. Across the African continent, many political and private organizational leaders operate within complex political, economic and social challenges. However, one persistent and intensely rooted problem is the prevalence of non-accountability. The failure to institutionalize transparency and responsibility has become a defining weakness in both the public service and corporate sectors. This systemic reluctance to lead with integrity, displayed in corruption, avoidance of responsibility for poor or unethical decisions and the misappropriation of public resources, undermines public trust and weakens governance structures. Consequently, such leadership deficits impede economic development, stifle organizational growth, erode nation-building efforts and compromise long-term effective sustainability.

Across Africa, the conversation about leadership is no longer confined to election seasons or policy debates. It has become a daily life experience, felt in the rising cost of living, the decay of public services, the anxiety of unemployed youth and the quiet exodus of skilled professionals. At the center of this experience lies a persistent and widely acknowledged problem: a deficit of accountability and transparency in public service, political and corporate leadership.

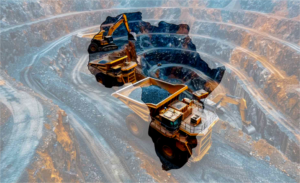

While Africa is not short of visionary ideas or natural resources, the gap between promise and performance remains stark. Investigations, audits and citizen testimonies repeatedly point to the same conclusion of weak accountability systems, entrenched corruption and leadership cultures that reward loyalty over competence, continue to dent development across the continent.

![]()

In many African political systems and corporate organizations, leadership operates within rigid hierarchies shaped by history, culture and power imbalance. Respect for authority is an important social value that can be morphed into enforced silence. Civil servants, corporate employees and even elected representatives often hesitate to question decisions, flag wrongdoings, or challenge inefficiency.

This reluctance is a frequent work/office culture in most establishment, moreso in Africa. Fear of retaliation, loss of livelihood, or political exclusion, keeps many quiet at the workplace. In both government ministries, boardrooms and management/administrative systems, mistakes are frequently buried rather than corrected. Whistleblowers face isolation. Accountability becomes selective. Propaganda is a politically systemic-crusade engineering. And the result is a façade of stability that masks deep institutional decay. Some political analyst would agree that silence is often rewarded more than integrity, in most systems/structures in Africa. But truth be told, when silence becomes the norm, mediocrity and corruption thrive.

The accountability crisis is most visible in politics, canvassing power without restraint. For instance, across some parts of the continent, some leaders cut across political cadres/appointments, who have overstayed their mandates/tenure, or influenced re-election repeatedly, they part of the human-ingredients who have weakened constitutional security in some nations, or manipulated electoral processes in others, etc.; and have created fertile grounds for instability. In recent years, military coups in some parts of the Africa continent, have justified rightly or wrongly, the public reactions to evacuate some political leadership.

Beside coups, the erosion of democratic norms manifests in implicative ways, such as compromised electoral commissions, politically-compromised court processes; and legislatures reduced to rubber stamps. Where institutions are weak, leaders operate with impunity. Public funds are mismanaged, oversight functions/budgets are sidelined; and citizens suffer, moreso left without effective channels for redress or even demonstrate their freedom of speech. The result in most cases is mass public street-reaction.

Ethnic and sectarian divisions, many of which were inherited from colonial governance structures, are often exploited to entrench power. Rather than serve as platforms for inclusion, sociocultural identity-politics becomes a tool for exclusion, fueling conflict and undermining national cohesion.

The accountability gap is not limited to government or civil service alone, there is the corporate leadership ill-profits by systemic maneuvering, budget padding, corrupt consultation-outsourcing, etc., without responsibility, integrity or consideration of the business founder.

In corporate Africa, similar patterns emerge. In both public enterprises and private firms, leadership failures that are ranging from opaque procurement practices to nepotism and regulatory evasion, always exist, undermining productivity, investment commitment and investors’ confidence.

State-owned enterprises, in particular, often suffer from political interference and poor governance. Appointments are made on loyalty rather than merit, leading to inefficiency and financial losses that ultimately burden taxpayers. In the private sector, weak enforcement allows some corporations to sidestep labour standards, environmental protections, tax obligations, expansive inequality and social resentment.

In respect to small businesses, the effects are severe. Bribery, inconsistent regulation, lack of transparency, etc., raise the cost of doing business, stifle innovation and discourage entrepreneurship, especially among young people.

The economic consequences of poor accountability are profound. Despite vast natural and human resources, many African countries remain trapped in cycles of poverty and underdevelopment. Mismanagement of public funds diverts resources from critical investments in infrastructure, education and healthcare. External debt continues to rise as governments borrow to cover gaps created by wasteful spending and weak revenue systems. Roads, power grids, hospitals and schools deteriorate or remain unfinished, constraining growth and limiting opportunities for millions. Corruption through embezzlement, misappropriation, illicit financial flows, drains billions of dollars annually from African economies. These losses translate directly into fewer jobs, weaker social safety nets, or intense dependence on loans/foreign aid.

At the grassroots level, the accountability crisis hits hardest. Families bear the cost of failing systems through out-of-pocket healthcare expenses, private schooling to replace collapsing public education, insecurity fueled by unemployment, rapid rising crime amongst the youth, etc. Youth unemployment remains one of the continent’s most urgent challenges. With limited opportunities at home, many young Africans turn to informal work, risky migration routes, or criminal networks. Others leave legally, contributing to a persistent brain drain that depletes African countries of professionals like doctors, engineers, educators, technovators, nurses, architects, lawyers, scientists, entrepreneurs, drivers, numerous talents, etc. Social trust erodes as inequality widens. When leaders are seen to operate above the law, ordinary citizens lose faith in the idea of fairness. Civic engagement declines and cynicism replaces hope.

Root causes from colonial legacies to modern scenarios. Analysts point to multiple root causes behind the leadership crisis. Colonial administrative systems centralized power and expanded ethnic divisions, fault lines that were never fully addressed after independence. Over time, many states inherited strong executives but weak institutions.

But wait a minute! Are our African leaders jokers? If we were handed over some misfit leadership structures, systems and constitutions, shouldn’t they have changed the narratives since the exit of the colonial masters, if they are not just wicked, evil-minded, corrupt, selfish, greedy and inconsiderate of their citizens and national development?

In the post-independence era, leadership in some contexts shifted from transformational visions of nation-building to transactional politics, where access to power is exchanged for loyalty and personal gain. Governance became personalized, and accountability mechanisms were hollowed out. So you would agree with most critical African minds that a turning point in this stead, calls for courage and deliverable service-minded reforms.

Despite the bleak picture, there are signs of resistance and renewal. Civil society organizations, investigative journalists, youth movements and reform-minded leaders are increasingly challenging the status quo. Across the continent, citizens are demanding transparency, service delivery, accountability and respect for the rule of law. Experts argue that lasting change requires more than new faces. It demands stronger systems. A total mind-reset-reorientation, non-influenced court processes, empowered anti-corruption agencies, credible electoral bodies and professional civil services are essentially needed to regerminate in this direction. In the corporate sector, robust governance frameworks and ethical leadership must replace patronage and service-opacity.

At the centre of these clamouring reforms, lies what many would describe as moral courage. The willingness of leaders to choose accountability, integrity, transparency and honour, when and where corruption is normalized and silence feels safer.

Africa’s development challenge is not a lack of ideas or talent, or human capital index. It is a leadership test that determines whether the continent’s future is shaped by shared prosperity or continued cycles of disappointment. The outcome will depend on whether accountability, integrity, transparency and honour become the foundation of the rule-of-engagement, not the exception.