EU’s €955bn Recovery Fund Nears Finish Line with Billions Spent, Reforms Promised and Uneven Impact

As Europe enters 2026, the European Union’s flagship post-pandemic recovery programme titled -NextGenerationEU (NGEU), is approaching its final phase with more than €182 billion still undisbursed. Launched in 2020 at the height of COVID-19’s economic shock, the €955 billion initiative was designed as an emergency lifeline, and as a once-in-a-generation push to modernise Europe’s economy, politics and social contract.

In human terms, the fund helped steady livelihoods during an unprecedented collapse in economic activity. It financed job protection schemes, supported public services under strain and channeled investment into sectors meant to future-proof the bloc, from clean energy to digital infrastructure. Particularly in southern Europe and for many other communities, it offered breathing space and a sense that Brussels could act decisively in a crisis.

Politically, NGEU marked a watershed. By embracing joint EU borrowing, long considered taboo, member states crossed a line that has since reshaped the union’s policy toolkit. What began as an emergency measure is now widely viewed as a precedent for collective fiscal action of an important shift, as Europe confronts geopolitical pressure, supply-chain vulnerabilities and growing economic competition from the United States and China.

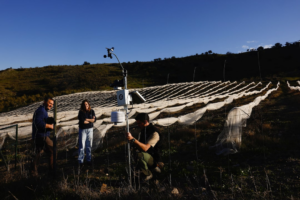

On the ground, the recovery fund’s ambitions are most visible in projects blending technology with everyday life. Across Spain’s olive groves and vineyards, sensors and drones collect soil and climate data to feed artificial intelligence systems that help farmers reduce water use, cut emissions and improve yields. Similar initiatives across the bloc reflect NGEU’s core promise, to link the green transition with digitalisation and to bring innovation into traditional sectors, which is already happening in some communities across Europe.

Juan Francisco Delgado, a coordinator of one such agricultural project said “The funds left us with data infrastructure, shared governance and teams capable of operating AI at scale. What they haven’t left us with is a business model”. As recovery money runs out, his team and like many others, are scrambling to secure long-term financing, upgrade equipment and retain skilled staff.

This gap between infrastructure and sustainability highlights a broader challenge. While more than €700 billion in grants and loans became available to member states from 2021, later reduced to €577 billion after some countries declined loans; and implementation has been slowed by complex approval processes, skills shortages and administrative bottlenecks. Five years on, economic growth across the Europe area remains sluggish, trailing both the US and China.

The European Commission insists the programme has met its objectives, pointing to reforms tied to funding; pointing to labour-market changes in France and Spain, faster renewable-energy permitting in Italy, Greece and Portugal; and cybersecurity upgrades in Eastern Europe. Economists also broadly agree that these measures could lift productivity over time. But delays in some sorts, have blunted any immediate growth boost; and outcomes vary sharply between countries.

Spain, citing supply-chain constraints and technical hurdles, renounced more than €60 billion in loans late last year, arguing that improved access to capital markets reduced the appeal of EU borrowing. Italy, the fund’s largest beneficiary, has spent about €110 billion so far, but lawmakers warn of a potential investment cliff once the programme ends. Rome has secured approval to spend €23.5 billion beyond the 2026 deadline, while Spain has repurposed €10.5 billion in loans, to unlock up to €60 billion in state-backed financing.

Spain, citing supply-chain constraints and technical hurdles, renounced more than €60 billion in loans late last year, arguing that improved access to capital markets reduced the appeal of EU borrowing. Italy, the fund’s largest beneficiary, has spent about €110 billion so far, but lawmakers warn of a potential investment cliff once the programme ends. Rome has secured approval to spend €23.5 billion beyond the 2026 deadline, while Spain has repurposed €10.5 billion in loans, to unlock up to €60 billion in state-backed financing.

Such flexibility may prove crucial. ING economist – Carsten Brzeski, said “Extending programmes by one or two years would be an easy way to ensure the money reaches the real economy”; arguing for looser fiscal rules when reforms strengthen long-term public finances. As deadlines loom, member states must complete reforms by late August and submit final payment requests by September.

The recovery fund’s legacy remains contested. It has reshaped EU politics, accelerated digital and green investment, and offered tangible benefits to communities and workers. However, whether it delivers lasting economic transformation, may depend less on how much money was spent, and more on what Europe builds after the funding runs out.