Namibia’s Economic Stability from Resources, Tourism and Aquaculture, Highlights Continuous Leverage of Historical Gains

When Namibia marked independence in 1990, the celebrations carried echoes far beyond its borders. In West Africa, Nigeria, which was then under military rule, had invested heavily in the dream of a free Namibia, backing the South West Africa People’s Organisation (SWAPO) with diplomatic muscle, sustained funding and a reported N100 million solidarity fund. To the Namibians who endured decades of colonialism and apartheid-era occupation that support was not abstract geopolitics. It was a support that filtered into refugee camps, family separations and the long wait for return.

Three and a half decades later, Namibia stands out in southern Africa as a relatively stable democracy with a modest but growing economy anchored in natural resources, tourism and fisheries. Yet, beneath this success story is a silent national conversation about who benefits, how history is remembered and whether liberation-era politics, still serve a changing society.

Founded on April 19, 1960, SWAPO emerged as a liberation movement opposing South Africa’s occupation of South West Africa. After years of fruitless international appeals, the movement turned to armed struggle in 1966 through its military wing, the People’s Liberation Army of Namibia (PLAN). Exile politics shaped SWAPO’s identity, with support from African states like Nigeria and frontline allies such as Angola, as well as backing from the Soviet bloc.

That history still matters at the grassroots. In northern Namibia, particularly among Ovambo communities that formed SWAPO’s early base, liberation credentials are woven into family stories of sons who crossed borders to train, mothers who hid their activists and villages disrupted by war. These narratives continue to translate into political loyalty, helping SWAPO maintain dominance since winning the first democratic elections in 1989.

But governing is different from resisting. Since independence, SWAPO has transitioned from a guerrilla organisation into an established ruling party, controlling parliament for more than three decades. Under founding President Sam Nujoma, Namibia prioritised national reconciliation, retaining many colonial-era institutions to avoid economic collapse. That pragmatism brought peace and investor confidence, but it also postponed profound structural change. An economy built on nature and cautious equilibrium.

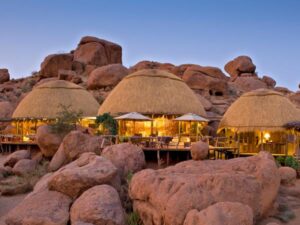

Namibia’s economy today rests on three pillars – mining, tourism and fisheries. Diamonds and uranium remain critical foreign exchange earners, while conservation-driven tourism has turned vast deserts and wildlife reserves into global attractions. Along the Atlantic coast, fisheries and emerging aquaculture projects, provide jobs and export revenue.

However, the benefits are uneven for many communities. Mining towns boom and bust, rural youth migrate toward cities with limited opportunities. While debates persist over foreign ownership and environmental impact. In fishing communities, over-exploitation scandals have raised questions about governance and who controls national resources.

These tensions feed into a broader reappraisal of independence-era compromises. Critics argue that while political freedom was secured, economic power structures still reflect colonial patterns. Supporters counter that stability itself is an achievement in a volatile region and a foundation for gradual reform.

Nigeria’s role and a Pan-African thread, was a selfless-national displayed act, where Nigeria’s support for Namibia’s liberation remains a point of diplomatic pride, often cited as evidence of Pan-African solidarity in action. Apart from fundings, Nigerian diplomacy amplified SWAPO’s case at international forums when Namibia’s struggle risked being sidelined by Cold War politics. As for most older Namibians, Nigeria is remembered as a state ally and distant partner that helped shorten the road to independence.

Today, that relationship is largely symbolic, as it offers lessons. It shows how African states once coordinated around shared liberation goals; and how that spirit could be repurposed towards trade, skills exchange, borderless transactions and regional development, rather than memory alone.

Between reverence and renewal, Sam Nujoma is widely revered as Namibia’s “Founding Father”, credited with steering the country towards peace and reconciliation. Current leadership, including President Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah, inherits both that legacy and the pressure to adapt. Younger Namibians, born after independence, are less concerned with their liberation history and more concerned about jobs creation, the ills of corruption and lack of inclusion.

The challenge for SWAPO and Namibia is not to erase the past, but to revisit it honestly. Historical reappraisal need not undermine independence, but strengthen it by widening the national story to include workers, coastal communities, women and youth whose struggles did not end in 1990.

Namibia’s stability is real, and its growth is tangible. The next chapter will depend on whether the country can translate its hard-won freedom, rich natural endowment and liberation solidarity into a more broadly shared future that is rooted as firmly in community needs as it is in national memory.