Zimbabwe’s Fiscal Growth and South Africa’s Prolonged Stall, Picture Two Different Economic Shocks

Over the past 15 years, two neighbouring countries with extremely intertwined histories have taken sharply different economic paths. Zimbabwe, long cited as a cautionary tale of economic collapse, has recorded far faster growth in recent times than South Africa, the continent’s most industrialized economy, whose output has barely moved in real terms.

Measured in US dollars, Zimbabwe’s economy has more than tripled since 2010, growing from about $12 billion to over $41 billion. South Africa’s economy by contrast, has slipped slightly over the same period, shrinking from roughly $417 billion to about $401 billion. The comparison is striking, even allowing for the vastly different starting points.

This growth has not erased memories of hardship for many Zimbabwean families though. The scars of hyperinflation, food shortages and mass emigration remain vivid. Parents who once queued for bread with wheelbarrows of near-worthless cash now cautiously acknowledge modest improvements in daily life, especially in informal trade, small-scale mining and agriculture. The recovery has been uneven and fragile, but it has changed the national conversation from survival alone to cautious rebuilding.

Zimbabwe’s turnaround comes after one of the most severe economic collapses in modern history. The fast-track land reform programme of the early 2000s, combined with costly military involvement in the Democratic Republic of Congo and years of policy uncertainty, hollowed out state finances. Inflation peaked at an estimated 231 million percent in 2008, wiping out savings and trust in public institutions. International sanctions and isolation compounded the crisis.

Yet, from this low base, the economy has expanded steadily over the past decade and a half. Analysts point to dollarization, the elasticity of informal markets, remittances from the diaspora and renewed activity in mining and agriculture as key drivers. SMEs and small family businesses that community-based, have filled gaps left by the state, creating a grassroots form of growth that rarely shows up neatly in official statistics, but sustains millions of households.

South Africa’s story on the other hand is different, and for many citizens, there is increasing frustration. As Africa’s largest and most diversified economy, it entered the 2010s with strong institutions, unfathomable capital markets and global credibility. Still, growth stalled. Corruption scandals, chronic electricity shortages, failing rail, crime and negative port systems; and rising regulatory complexity steadily eroded investors’ confidence.

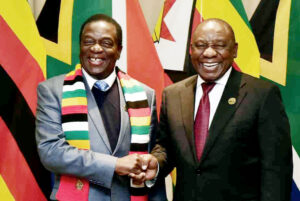

President Cyril Ramaphosa and the African National Congress (ANC) frequently highlight that the economy has tripled in size since the end of apartheid in 1994, and that employment has more than doubled, from around 8 million to over 16.7 million people. These gains are real and historically significant. But they coexist with a harsher reality; unemployment has surged because growth has not kept pace with population increases and new entrants to the labour market.

Over the last 15 years alone, South Africa’s GDP has effectively flatlined. The consequences are felt in households across the country. Young graduates unable to find jobs. Small manufacturers squeezed by unreliable power. And families are stretched by rising living costs. While political leaders celebrate long-term milestones, many voters measure progress by what they experience daily.

Economists point to declining investment as a central problem. South Africa’s gross fixed capital formation, investment in infrastructure, machinery and productive assets, have fallen from around 30% of GDP in the 1970s to about 15% today. By comparison, many emerging-market peers, invest closer to 25%. Without sustained investment productivity stalls, wages stagnate and job creation slows.

Investec strategist Osagyefo Mazwai argues that restoring business confidence is the most affordable and effective form of economic stimulus. “Confidence drives investment, and investment drives growth and jobs”, he says. South Africa’s own history shows a strong link between optimism in the private sector and improved economic outcomes. He noted that the challenge is political as much as economic, pinning it on lack of credible reforms, reliable infrastructure and policy consistency.

The contrast with Zimbabwe does not mean Zimbabwe has overtaken South Africa in prosperity or living standards. Per capita income remains far lower, public services are strained and governance concerns persist. But the comparison does highlight how damaging a prolonged stagnation can be, for a country with far greater resources.

Politically, the divergence carries weight. It sharpens debates about accountability, reform and the future direction of economic policy for South Africa., However contested for Zimbabwe, it offers the ruling authorities evidence that recovery is possible. Even then, civil society groups warn against complacency and call for stronger institutional reforms.

Both countries reveal a common thread socioculturally, showing how ordinary people adapt, where systems/structures fall short of productivity. From township entrepreneurs in South Africa to cross-border traders/farmers in Zimbabwe, growth and survival often happen one way or the other snailishly, despite economic state of things.

Fifteen years on now, the lesson from this regional comparison is less about celebrating one country over another, but more about the cost of lost momentum. Economic potential once stalled, is hard to restart even though it could be restarted. And for families on both sides of the Limpopo, growth is not an abstract statistic, it is the difference between delayed hope and a slowly returning of it.