Africa’s Abundant Minerals, but Limited Gains: The Paradox of Plenty in Mineral-Rich Countries

Gold production has resumed at the Loulo-Gounkoto complex in western Mali, bringing an end to several months of uncertainty for one of the country’s most strategic mining sites. The shutdown followed a January standoff in which the Malian government blocked exports from the Canadian-owned Barrick Mining operation and seized three tonnes of bullion over allegations of unpaid taxes.

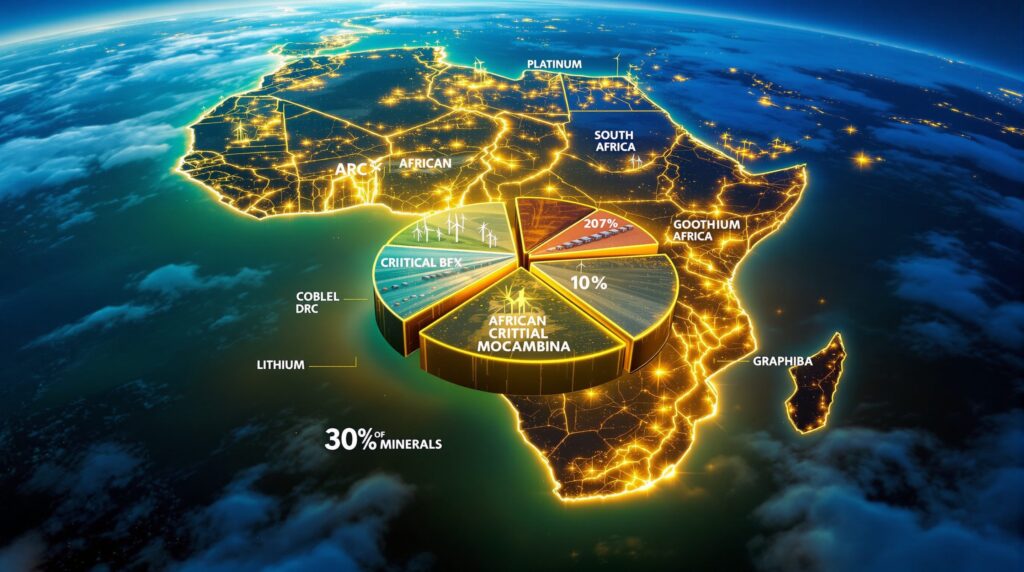

The specifics of the legal dispute remain contested, but the episode highlights a much wider problem across the African continent. Africa mineral-rich countries often fail to benefit commensurately from their own natural resources.

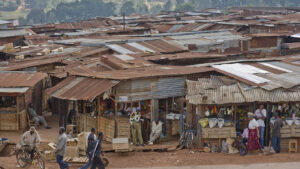

The International Monetary Fund estimates that multinational mining companies’ tax avoidance costs African governments between US$470 million and US$730 million every year. These are funds that could otherwise be channeled into developments of roads, power infrastructure, clinics, schools, etc. In regard to many communities living near mining sites, the distanced-disconnecting between the wealth extracted from their lands and the services they receive is awfully mind striking. Partly worse-off, families still travel long distances for healthcare, children learn in overcrowded classrooms without proper amenities, and local economies rarely diversify energy for financial benefits beyond the mines themselves.

The human implications are far-reaching. When mining revenues fall short, governments struggle to provide the basic support that stabilises households, like clean water, reliable electricity, meaningful job opportunities, social bailout-palliatives and so on. This fuels frustration in communities that bear the environmental costs of mining, hosting dust, pollution, and land degradation, while seeing little direct benefits.

Culturally, disputes over resource revenue tap into indepth questions about sovereignty and ownership. Minerals are often treated as a shared national inheritance, yet many citizens feel that decision-making about how these resources are taxed, managed and negotiated, remains distantly cloudy. The perception that foreign companies profit while local communities struggle, reinforces longstanding anxieties about unequal global power relations.

From a business perspective, the tensions create an unpredictable investment environment. Mining firms point to unstable regulations, sudden tax claims, including political uncertainty, as barriers to long-term planning. Meanwhile, African governments argue that profit-shifting and overly complex accounting structures such as those flagged by the Intergovernmental Forum on Mining and the OECD, undermine their ability to collect fair revenue. Practices like abusive transfer pricing/artificial profit-shifting, drain national budgets, weakening trust on both sides.

![]()

Administratively, some disputes like Mali’s can become a rallying points to take directions. Leaders often face public pressure to renegotiate contracts or take a tougher stance with foreign companies, especially during moments of economic hardship or rising unrest. While this can boost political capital domestically, it can also strain relations with investors, triggering disruptions that can affect jobs, even local supply chains.

The consequences ripple outward socially. Mining regions frequently remain underdeveloped, despite decades of mining, sociostatus disparity and sociocultural tensions. Demography of the youth, who make up the majority of the population in many sub-Saharan countries, often find themselves excluded from the wealth generated from their homeland. This circumstances gives birth to migration pressures and political dissatisfaction.

A longline of mixed factors explains why many mineral-rich African nations are not reaping the rewards they expect. Some of these elementary factors are unequal bargaining power in negotiations, outdated or weak legislation, limited auditing capacity, political systems vulnerable to corruption/short-term decision-making, insincere governance in Africa, amongst others. The result is a persistent mismatch between the continent’s natural resources wealth and the wellbeing of its people.

The broader question remains resounding – How can African countries convert mineral abundance into shared prosperity and industrialized diversities, rather than isolated disputes?

Until African government decolonize herself, become selflessly considerate of her citizens, abhor corruption, beget stronger transparent revenue systems, migrate from the beggarly-urge for foreign debt accruement to thinking inwardly and host corporate practices more accountable, the promises from Africa’s mineral wealth, will continue to outpace its reality.