Africa’s Green Mineral Surge: Can the Continent Meet Quadrupling Demand without Repeating Old Mining Mistakes?

Mary’s daily rhythm begins long before dawn for the sake of six of her eight children in DRC. Walking barefooted over cracked red soil, she guides them past dry river beds toward the twinkling lights of the nearest mining camp in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). Here, cobalt ore that is essential for making electric vehicle batteries, lies just beneath their feet, yet almost none of its promise reaches their plates, fends for their schools, or their futures. Across Africa, stories like this African mother, are becoming more familiar.

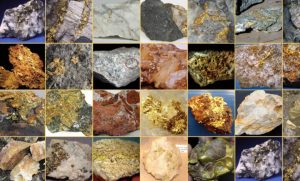

Global demand for metals like lithium, cobalt, nickel, manganese, graphite, uranium, rare earth elements, etc., is poised to quadruple by 2040, if the world is to meet the Paris Agreement targets for curbing climate change. Roughly a fifth of these critical minerals reserves are in Africa. The continent is rich in raw metal, but poor in regulatory, leadership, political-will, governance and infrastructural power. The question now is, as mining expands, will the extraction follow the old, exploitative pattern, or will it be done differently? Drawing a cue from families like Mary’s in Africa, to the global business lines.

In Mary’s concern, cobalt mining means early wake-ups and endless toil. But then, for major multinational firms, governments, investors, etc., cobalt is one axis in the multi-trillion-dollar clean-energy economy being built. The minerals powering batteries, electric cars, solar panels, and wind turbines are the new black oil spinners; such that Africa’s reserves are now drawing unprecedented geopolitical and corporate interest. This interest comes with tension. On one hand, business and government leaders see opportunity in creating jobs, generating revenue, developing infrastructure and positioning for global relevance. In Zambia and South Africa, for example, efforts are now under way to move past mere extraction and toward value addition, innovation and local processing of these critical minerals. On the other hand, families like Mary’s often face the costs of gender manipulations, child labor, unsafe conditions, poor compensation, land loss, environmental degradation and exclusion from decision-making.

There are resounds of political stakes and social pressure that are making African civil society and concerned local-stakeholders not to play silence over this commonwealth. Across the continent, activists, community leaders, opinion polls and NGOs are asking for concrete changes in how mining is done and its resultant-effects to Africans. These changes should define who benefits; what development should happen; who should/shouldn’t be included in making decisions; how the environmental and social costs are borne; and enforcements, etc. Some of the key demands are:

- Ensuring free, prior and informed consent for communities, especially Indigenous peoples and peasants living where mineral reserves have been identified.

- Sharing revenues more equitably, including royalties, community development projects, local procurement and infrastructure.

- Enforcing higher environmental standards/developments so that deforestation, water pollution and biodiversity loss are minimized.

- Ending exploitative labor practices, including child labor and improving workplace safety.

- Encouraging local innovation, ownership and value addition within the mining location-point, not just exporting raw ores, etc.

Politically, this demand for change is colliding with existing frameworks and incentives. Many African states have laws and regional agreements on paper, for instance – the Africa Mining Vision and Minerals Governance Frameworks, but enforcement is weak. Corruption, limited regulatory capacity, political instability, lack of political-leadership will and sustained dependence on foreign capital, has made meaningful changes difficult to be realized in this regard, over time.

On a second thought, rural residents/family-owned mining practices are emerging as interested actors, powered by companies that materialistically affect how wealth is used in local communities. Some are driving improvements in employer practices, local education, infrastructure, etc. But then again, even these acts are up against system and structures, causing capital constraints, technological limitations and regulatory hurdles, in which larger players often absorb more easily.

Take for instance, the artisanal miners who are often some knot of families or small groups who dig by hand, presume the raw geology is everything to them. Still, they often do not have any form of safety nets, no formal contracts, let alone any means of better bargaining power. When prices rise or companies move in, displacement or environmental damage hit them hardest at most times. Their supposed “success” in many cases, which inspires their daily-drive for the mining field, is just SURVIVAL. This is one of the inner fiery-intravenuosness that makes Mary’s daily walk to the mine field, a symptom of the global supply chain that often treats the last mile of extraction, same as from the onset.

The ramp up in demand for clean-energy minerals, carries serious environmental risks. Forests are cleared, rivers contaminated and protected lands sometimes reclassified. In Madagascar for example, endemic species already under threat may face further habitat loss due to mineral projects. Also, mining’s pollution licks like lead, mercury, acidic runoff, can impose long-term health costs on nearby communities.

In many locations, the social contract is fraying. Communities displaced from land, lose livelihoods, traditional knowledge and cultural practices. Schools, clinics, potable water, which are promised in many agreements, repeatedly fail to materialize, or do so only minimally. Children may end up working in mines rather than attending school, as is already happening in certain lithium mining zones in West Africa and some parts of Africa.

The limits and signs of shifting grounds must begin to ascend in Africa. Though, some indicators are positively showing that decisions like the following below might have started taking place:

- Policy momentum: Countries like Zambia and South Africa are establishing critical minerals strategies. These aim not just to extract, but to process, innovate and capture more value domestically.

- Civil society pressure: Communities are organizing reports, raising lawsuits, demanding accountability. The notion of – JUST TRANSITION, is gaining traction among NGOs and in state policy.

- Gender transformations: In places like the DRC, women are claiming more control, for example through the – MOTHER BOSS movement in artisanal mining pits, which is reshaping power dynamics in mining zones.

- Social ownership models: In places like Sekhukhune South Africa, mining-affected communities are exploring forms of socially owned renewable energy as an alternative model. One where the community controls energy, infrastructure and benefits, besides mining firms.

But significant constraints remain, such as the cost of financing large mines or downstream processing, weak legal enforcement, foreign firms dominating investment/supply chains, pressures to deliver returns fast; and sometimes the lacking of or inconsistent political-leadership will.

What real shift-changes should look like: for the mining boom to become a force for sustainable development rather than renewed extraction, several changes would be essential:

- Stronger legal frameworks and enforcement: laws must require community consent, protect lands, limit environmental damage and enforce labor protections: authorities must have the capacity to monitor, enforce and penalize violations.

- Community inclusion and agency: from the earliest stages, the people who live where minerals are found should be partners/decision-makers and not only recipients of compensation, but of opportunity like jobs, ownership, skill-acquisitions, local businesses, etc.

- Value addition locally: instead of exporting raw ore or other minerals, build refineries locally, enable local processing, establish manufacturing capacity in Africa, etc., so that more of the value chain stays and benefits stay locally in Africa.

- Environmental safeguards: Protections for ecosystems, water sources, public health; mechanisms to ensure remediation and restoration; and transparent impact assessments.

- Transparent financial arrangements: clear and fair contracts, royalties, profit-sharing; monitoring of revenue flows to avoid corruption and ensure that benefits are visible in community development.

- Alternative and complementary livelihoods: so that communities are not wholly dependent on mining alone but investments in agriculture, education, small businesses, renewable energy infrastructure, etc., can diversify risk.

- Gender equity and social inclusion: ensuring women are included not just as laborers, but in leadership; ensuring marginalized groups are heard; and protecting children from harmful labor.

The transnational Africans such as indigenous residents of lands where natural minerals’ fields are, like Mary in DRC, would have inner-rumbling questions, wondering what world their children will be stepping into with all these limitations in place, inspite of the God’s natural wealth beneath their feet. Will they have schools to attend or will they be able to go to school? Will they see infrastructures to use? Will they see electricity from clean energy to use? Or will their land, water, socioculture lie scarred and their future sold to powers far away?

The clean energy revolution depends on minerals, but if history provides any present guide, history’s wounds will risk being replayed with only new labels.

Africa holds a deep reservoir of potentials, not only in the earth, but in generations of families and communities who have long lived with mining’s promises, betrayals, and are treading on the mineral resources daily. The coming decades may decide whether the clean-energy wave will indeed lift them from poverty in total, or wash them away.