Africa’s New Age Leaderships: Current Governments, Dynamic Political Shifts, Powering Growth and Global Influence in 2025

In 2025, Africa stands at a fascinating intersection of an intricate mosaic of old and new political-leadership/juntas power, where civilians thrive as political-leaders in their will, monarchs coexist with reformists, soldiers rule in junta regimes, military men become democrats in presidential space and the continent’s heartbeat of leadership power pulses with the rhythms of both continuity, transition and change. From Cairo to Cape Town, from Dakar to Dar es Salaam, Niger to Burkina Faso, Senegal to Nigeria, Botswana to Madagascar, leadership in Africa today reveals as much about the continent’s past struggles as it does about its future ambitions. This is a continent in active-dynamic motion.

Africa’s 54(+1, whether recognised or not) nations present a kaleidoscope of governance structures, presidential republics, constitutional monarchies, transitional governments, seat-tight continuous presidents and one-party states. Each leader in their own way, embodies a fragment of the continent’s complex political DNA. In North Africa, veteran rulers like Egypt’s Abdel Fattah el-Sisi and Algeria’s Abdelmadjid Tebboune preside over nations balancing economic reform with tight political control. Morocco’s King Mohammed VI, ever the symbol of stability, continues to blend tradition with modernization, while Tunisia’s Kais Saied charts a more unpredictable path through populist rule.

Further south, in the vibrant and often tumultuous heart of Sub-Saharan Africa, the political landscape unfolds with remarkable complexity, a living interplay of democratic endurance, recurring military interventions and subtle yet profound decolonial shifts in the nature of governance and leadership. Across countries, different trajectories expose both the strains and the possibilities of this transformation, to mention but a few:

In Mali, Colonel Assimi Goïta, leader since the 2020 and 2021 coups, now serves as President of the Transition. His regime has repeatedly delayed elections, arguing persistent security threats from jihadist insurgencies demand more time.

In Burkina Faso, Captain Ibrahim Traoré, following coups in 2022, has assumed the interim presidency under a junta regime. His government has extended its transition beyond initial promises, leaning into rhetoric of sovereignty, anti-imperialism, and local leadership, while also facing intense pressure from violent insurgency and humanitarian challenges.

In Gabon, Brice Clotaire Oligui Nguema, who came to power via a coup in 2023, was formally elected president in April 2025 with an overwhelming majority. His rise marked the end of the Bongo family’s decades of long rule, and his early presidency signals both continuity with the past (military involvement) and a break, especially in how he has pledged reforms, greater economic sovereignty, and institutional changes.

In Guinea, General Mamady Doumbouya came to power in a 2021 coup, deposing President Alpha Condé. Since then, his regime has promised a return to civilian rule, withheld or delayed transition deadlines, and is currently preparing for constitutional and presidential elections in December 2025 under a draft constitution that might allow him to run.

In Niger, General Abdourahamane Tchiani leads the National Council for the Safeguard of the Homeland, having taken power in 2023 via coup. He has been sworn in under a transition charter, dissolved existing political parties, and promised a transition over several years. Etc.

These cases illustrate the dual strains at work:

Democratic resilience: even in places under military rule, there remains popular demand for accountability, elections, constitutional order, and leaders who are responsive to citizens. In some countries, opposition movements, civil society, and regional organizations like ECOWAS continue to press for these democratic norms.

Military intervention: the reappearance of coups and junta rule in multiple states show that when democratically elected leaders are perceived as failing, especially around security, corruption, or external dependency, the military steps in. These interventions often come with promises of temporary rule, transition charters and restoring order.

Quiet decolonial revolutions in leadership culture: beyond just who holds power, there is change in how leaders talk, how they present legitimacy, and how they engage with colonial legacies. For example: rejecting old electoral institutions, rewriting constitutions, suspending or redefining political party roles, emphasizing sovereignty (particularly vis-à-vis former colonial powers), reasserting cultural identity, and redefining state symbols and foreign relationships.

In all these cases, the tension is palpable: on one side is the legacy of colonial borders, external influence, long entrenched regimes and on the other hand, growing demands for leadership that is not only locally accountable, but culturally rooted, nationally oriented, and ready to redefine what political legitimacy means. The current presidents are individually grappling with this dual legacy. Wrestling with foreign expectations and financial dependencies even as they try to reshape national narratives, reclaim sovereignty and respond to citizens who increasingly expect more than mere stability.

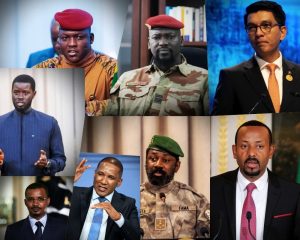

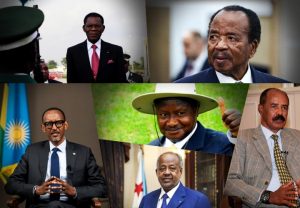

Below are the names (to the face-placements by your decision) of current African Leaders in power in 2025:

| Northern Africa

· Algeria: Abdelmadjid Tebboune · Egypt: Abdel Fattah el-Sisi · Libya: Mohamed al-Menfi (Presidential Council) · Mauritania: Mohamed Ould Ghazouani · Morocco: King Mohammed VI · Sudan: Abdel Fattah al-Burhan (Transitional Sovereignty Council) · Tunisia: Kais Saied

|

Central Africa

· Angola: João Lourenço · Cameroon: Paul Biya · Central African Republic: Faustin-Archange Touadéra · Chad: Mahamat Déby · Republic of the Congo: Denis Sassou Nguesso · DR Congo: Félix Tshisekedi · Equatorial Guinea: Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo · Gabon: Brice Clotaire Oligui Nguema · São Tomé and Príncipe: Carlos Vila Nova

|

Southern Africa

· Botswana: Mokgweetsi Masisi · Eswatini: King Mswati III · Lesotho: King Letsie III · Namibia: Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah · South Africa: Cyril Ramaphosa · Zambia: Hakainde Hichilema · Zimbabwe: Emmerson Mnangagwa

|

| Western Africa

· Benin: Patrice Talon · Burkina Faso: Ibrahim Traoré · Cape Verde: José Maria Neves · Côte d’Ivoire: Alassane Ouattara · Gambia: Adama Barrow · Ghana: Nana Akufo-Addo · Guinea: Mamadi Doumbouya · Guinea-Bissau: Umaro Sissoco Embaló · Liberia: Joseph Boakai · Mali: Assimi Goïta · Niger: Abdourahamane Tchiani · Nigeria: Bola Ahmed Tinubu · Senegal: Macky Sall · Sierra Leone: Julius Maada Bio · Togo: Faure Gnassingbé

|

Eastern Africa

· Burundi: Évariste Ndayishimiye · Comoros: Azali Assoumani · Djibouti: Ismaïl Omar Guelleh · Eritrea: Isaias Afwerki · Ethiopia: Sahle-Work Zewde · Kenya: William Ruto · Madagascar: Andry Rajoelina · Malawi: Lazarus Chakwera · Mauritius: Prithvirajsing Roopun · Mozambique: Filipe Nyusi · Rwanda: Paul Kagame · Seychelles: Wavel Ramkalawan · Somalia: Hassan Sheikh Mohamud · South Sudan: Salva Kiir Mayardit · Tanzania: Samia Suluhu Hassan · Uganda: Yoweri Museveni |

Across the continent, 2025 has become a year of reckoning for African leadership. Military takeovers in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger have tested the resolve of regional blocs like ECOWAS, while in East Africa, Tanzania’s Samia Suluhu Hassan and Namibia’s Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah have broken glass ceilings. Two women at the helm of nations long defined by male dominance. Their leadership marks a symbolic, if slow, shift toward gender inclusion in high politics.

Across the continent, 2025 has become a year of reckoning for African leadership. Military takeovers in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger have tested the resolve of regional blocs like ECOWAS, while in East Africa, Tanzania’s Samia Suluhu Hassan and Namibia’s Netumbo Nandi-Ndaitwah have broken glass ceilings. Two women at the helm of nations long defined by male dominance. Their leadership marks a symbolic, if slow, shift toward gender inclusion in high politics.

In contrast, the endurance of figures like Cameroon’s Paul Biya, now over four decades in power; and Equatorial Guinea’s Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, the world’s longest-serving president, illustrates the stubborn persistence of political longevity. Many citizens have come to see these leaders more as institutions than they appear as individuals, with their rule shaping entire generations, whether to the left or right. A self-righteous leadership odyssey of democracy, development, and massive expectations of evidential-realization of the African dream.

Beneath the headlines of coups and constitutions lies a quieter story. One of transformation. Kenya’s William Ruto and Zambia’s Hakainde Hichilema represent a new generation of pragmatic leaders focused on digital innovation, entrepreneurship and economic reform. Their message resonates with Africa’s youth that is over 60% of the continent’s population. People who are increasingly impatient for jobs, development, justice, genuine change and freedom of expression in all ramifications.

Meanwhile, countries like Rwanda and Ghana continue to draw attention for governance and infrastructure development, even as debates persist about human rights and political freedoms. Ethiopia’s Sahle-Work Zewde, Africa’s only female head of state, remains a moral voice amid the turbulence of ethnic conflict and reform.

In between tradition and transition, monarchies like Morocco, Lesotho and Eswatini, traditional authority blends uneasily with modern governance. King Mohammed VI’s social reforms contrast sharply with King Mswati III’s lavish lifestyle in a nation grappling with poverty and dissent. Yet, these monarchies last in reigns, offering cultural continuity in rapidly changing societies.

Across fragile states like Sudan, Libya, and South Sudan, transitional councils and uneasy coalitions are attempting to hold nations together after years of war and upheaval. These societies behold leadership as existential reality with expectation, not just a political structure.

Africa’s political map in 2025 tells a story of contrasts. Life-playing reformists beside autocrats, generals beside democrats and kings beside elected presidents. Yet, the through-line connecting them all is the urgency of governance that delivers on education, healthcare, climate resilience, infrastructure developments, industralisation and economic empowerment.

The question facing Africa’s over 1.4 billion people is not just who leads but how they lead. As global powers compete for influence across the continent, from China’s infrastructure investments to Western partnerships on security and green energy, the choices African leaders make today will determine the shape of the continent’s sovereignty and destiny for decades to come.

In the end however, leadership in Africa remains deeply human; rooted in family, faith, ambition, culture and the perennial struggle to reconcile power with purpose. And as 2025 rolls towards the end, Africa’s leaders, new and old, are being watched by us their citizens and by a continent yearning for its long-promised renaissance.