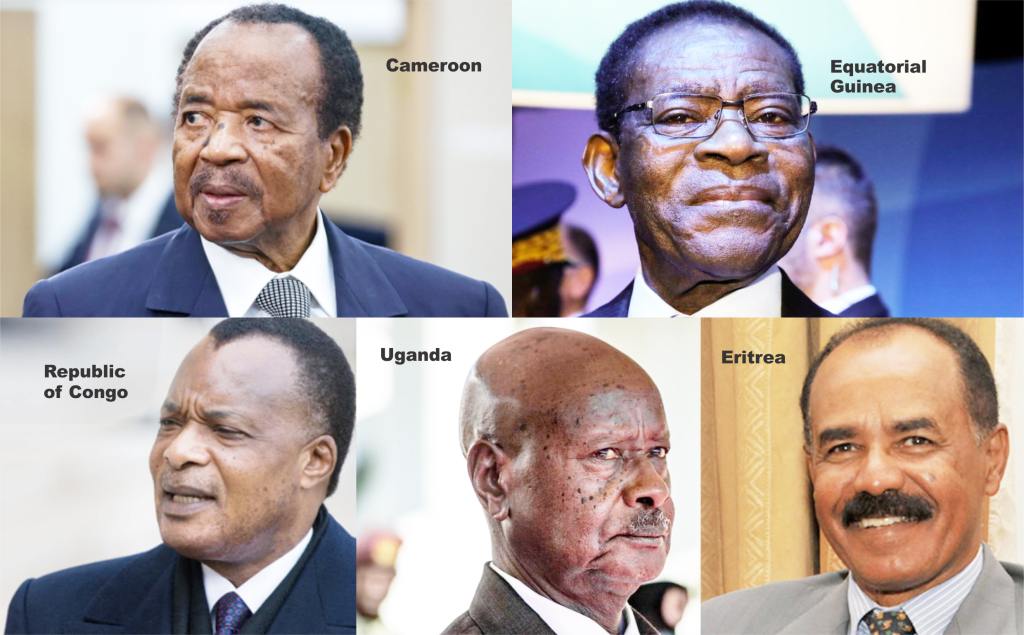

Africa’s Presidents for Life: The Five Men Who Have Ruled for Over 30 Years

The year 2025 still host five ‘ancestor-ish’ political-leaders who are standing as living monuments to Africa’s complex relationship with power. Male-presidents whose reigns have outlasted generations, economic cycles and entire political/military eras across parts of Africa. They have ruled their nations for almost two centuries. Their portraits hang in every government office. Their voices dominate national news. And their names have become synonymous with authority itself.

These leaders in profile, from Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo of Equatorial Guinea, Paul Biya of Cameroon, Yoweri Museveni of Uganda, and Isaias Afwerki of Eritrea to Denis Sassou Nguesso of the Republic of Congo, have one thing in common – their refusal to leave power; and their fortunate dodging of death althrough now.

| President | Country | Years in Power | Age | First Year in Office |

| Teodoro Obiang | Equatorial Guinea | 46 | 83 | 1979 |

| Paul Biya | Cameroon | 43 | 92 | 1982 |

| Yoweri Museveni | Uganda | 39 | 80 | 1986 |

| Isaias Afwerki | Eritrea | 32 | 79 | 1993 |

| Denis Sassou Nguesso | Republic of Congo | 28 (40 total) | 81 | 1997 (also 1979–1992) |

Average Age: 83 years

Average Tenure: 38 years

Notable Fact: Teodoro Obiang is currently the world’s longest-serving president still in office.

In Malabo, Equatorial Guinea’s capital, Teodoro Obiang’s image is ubiquitous, smiling down from billboards, on official portraits and even currency notes. He seized power from his uncle in a bloody 1979 coup and has since built a dynasty. His son, Teodoro “Teodorín” Nguema Obiang Mangue, serves as vice president and heir apparent. The country, one of Africa’s smallest by population but richest in oil, has become a family enterprise where loyalty is currency and dissent a dangerous gamble.

In Cameroon, 92-year-old Paul Biya governs largely from behind closed doors. Rarely seen in public, he splits time between the presidential palace in Yaoundé and a luxury hotel suite in Geneva. His long absence from public life has fueled speculation and quiet frustration among citizens who have never known another leader since 1982. Yet, his political machinery remains remarkably intact, maintained by a loyal elite who benefit from the status quo.

In Uganda, Yoweri Museveni once embodied Africa’s hope for democratic renewal. When he overthrew Milton Obote in 1986, he promised “a fundamental change” in governance. Four decades later, he remains in charge. His image older, his rhetoric more defensive. Constitutional amendments scrapped presidential term and age limits, clearing the way for his indefinite rule. His son, General Muhoozi Kainerugaba, now a senior army officer, has made no secret of his own presidential ambitions. For many Ugandans, the revolution that began with youthful idealism has become a family affair.

Similarly, Isaias Afwerki of Eritrea has ruled since the country’s independence in 1993 without elections, parliament, or a free press. His government, one of the most secretive in the world, runs on a system of indefinite national service that critics call “modern-day slavery.” Yet, among supporters, Afwerki is still revered as the father of the nation. This president, is man who built a state out of struggle and has kept it fiercely independent in a volatile region.

![]()

The Republic of Congo’s Denis Sassou Nguesso offers another version of the African strongman story, who is marked by his comebacks. He ruled first from 1979 to 1992, returned via civil war in 1997, and has remained ever since. At 81, he is one of the few leaders to have outlasted both the Cold War and the ideological tides that came after. His political longevity, supporters argue, has ensured peace; critics counter that it has stifled renewal and deepened inequality.

Across these nations, the narrative is complex. Stability has often come at the expense of democracy. The absence of term limits has blurred the line between leader and ruler, between patriotism and personal power. While each man’s story is rooted in a different history such as colonial legacies, liberation wars, or coups, all of them together form a patterned inscription – power in Africa, once gained is rarely surrendered.

In 2025, as the world debates leadership renewal and generational change, these presidents remain fixtures of the African political imagination. Some hold-tight-to-power resilient patriarchs of a past era, still defining the present directives even for a class people that comprise the Gen-Z, Gen-Alpha, Generation Beta, etc. While for the following class of people such as the Greatest Gen, Silent Gen, Baby Boomer Gen, Gen X and Millennial Gen Africans, many of whom were born decades into these men’s rule, the idea of democratic-political transition is almost theoretical to them.

Whether history will remember them as stabilizers who held fragile states together or autocrats who overstayed their welcome, is dependent one enduring truth – their long shadows continue to shape the political and social landscape of the continent indifferently.