Australian Scientists Move Closer to Restoring Sight with World-First Bionic Eye

In laboratories at Monash University, researchers are working on what could become one of the most transformative medical breakthroughs of the decade. A bionic eye system designed to restore vision to people living with profound blindness.

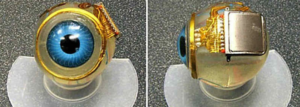

The device, known as the Gennaris Bionic Vision System, is being described as the world’s first neurotechnology capable of bypassing damaged optic nerves entirely. Instead of attempting to repair the eye itself, the system sends visual signals directly to the brain’s visual cortex, the area responsible for processing sight. This is a scientific-miracle for millions of people worldwide, who have lost vision due to injury, disease or degeneration. This invention would redefine what recovery means. But, let us look at how it works, and why it is a different health-tech.

The Gennaris system combines wearable and implanted technology. A miniature camera mounted on a pair of glasses, captures the surrounding environment. That information is processed and transmitted wirelessly to as many as 11 small implants placed on the surface of the brain. Each implant, roughly the size of a fingernail, stimulates the brain cells using carefully calibrated electrical pulses. The result is not simply flashes of light. Researchers say users are expected to perceive basic shapes, outlines and spatial information within a 100-degree field of view, significantly wider than many earlier visual prosthetics. While the restored vision will not replicate natural eyesight in full detail, it may allow users to navigate spaces independently, detect obstacles and recognize large objects.

After nearly a decade of laboratory development and successful animal trials, human clinical trials are scheduled to begin in Melbourne. These trials will be critical in determining how safely and effectively the implants function in real-world conditions, transcending the Laboratory.

The feel of independence for visually impaired people, often hinges on assistive technologies, mobility training and community support. Vision loss can limit employment opportunities, increase reliance on caregivers and heighten social isolation. Advocates say technologies like Gennaris could have ripple effects beyond medical outcomes. Greater mobility may open doors to education, workplace participation and social engagement. Families could see reduced caregiving burdens. Communities may need to rethink accessibility standards, if new forms of partial vision become possible.

Still, the researchers caution against premature optimism. Outcomes will depend on factors such as nerve health, brain adaptability and long-term implant stability. Largely, in respect to any brain-interface technology, questions about cost, accessibility, ethical oversight and equitable distribution always surmount.

The project also beckons to a broader neurotechnology moment, in biomedical engineering. By stimulating the brain directly rather than repairing peripheral organs, scientists are pushing the boundaries of neural interface research. This approach could inform treatments for other neurological conditions, if successful. Medical experts emphasize that large-scale trials are still needed before the device can be widely adopted. Also, regulatory approvals, surgical training and affordability will determine how quickly the technology moves from experimental promise to clinical reality.

In the meantime, the work at Monash represents a significant milestone for many living with visual impairedness. As it also offers something both scientific and extremely human, which is the possibility for a visually impaired person to see the world again.