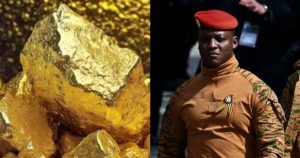

Burkina Faso Reclaims More from Gold Sector with Bold Mining Reform

In the heart of West Africa, Sahel region, gold is more than a precious metal, it is one of the lifelines of Burkina Faso’s economy. A source of livelihood for thousands and a pillar in the government’s efforts to navigate security and developmental challenges. This week, Burkina Faso made a bold step to claim a greater share of that lifeline.

The country’s largest gold producer, West African Resources (WAF), announced it has formally implemented the revised 2024 mining code by raising the government’s free carried equity stake in its gold projects from 10% to 15%.

For Burkina Faso, the move is more than a technical adjustment. It represents an economic recalibration, a political assertion of sovereignty, and a social wager on whether the nation’s gold wealth can translate into tangible benefits for ordinary Burkinabè.

From a business standpoint, the impact is already measurable. WAF, one of the country’s most significant foreign investors, recorded a financial accounting impact of a $33.4 million in its interim report for June 2025. While the adjustment trims into shareholder value, the company maintains that it remains committed to long-term operations in Burkina Faso, where it has invested heavily in exploration and production.

Mining analysts note that the increase in government equity comes at a time when global gold prices remain strong, giving the country more fiscal breathing room without necessarily discouraging investment. Still, foreign investors will watch closely to see how consistently the new code is applied and whether Burkina Faso continues to offer stability in a region where risk premiums remain high.

Politically, the revised mining code is emblematic of a broader shift across Africa, where governments are seeking to capture more value from natural resources long dominated by foreign firms. For Burkina Faso’s transitional authorities, grappling with insurgency and political instability, asserting a larger stake in gold revenues is also a way of reinforcing sovereignty.

Officials in Ouagadougou frame the policy as a matter of fairness: why should a nation ranked among the world’s top gold producers still face chronic budget shortfalls? By raising the government’s share, leaders hope to demonstrate to citizens that the state is taking concrete steps to defend national interests and secure resources to fund security and social programs.

For the average Burkinabè, gold mining is a double-edged sword. On one hand, large-scale mines provide jobs, infrastructure, and community investment. On the other, the industry has often been criticized for limited trickle-down benefits, environmental degradation, and the displacement of artisanal miners.

The new mining code raises expectations that increased government revenue will translate into improved services such schools, clinics, social welfare and rural development projects. Families in mining regions hope that this time, the wealth extracted from their soil will not bypass them.

Civil society groups have already called for transparency mechanisms to ensure that the additional funds do not disappear into corruption or remain concentrated in urban centres, far from the communities most affected by mining.

Beyond economics and politics, the security dimension looms large. Burkina Faso is battling one of the world’s most acute insurgencies, with violence displacing more than two million people. Gold revenues have become an essential lifeline to sustain military operations and humanitarian responses.

By raising its equity stake, the government gains not only more funds but also more leverage in negotiating how mining companies operate in conflict-affected zones. Ensuring that revenues are used effectively will be crucial to both maintaining investor confidence and addressing the grievances that fuel instability.

Burkina Faso’s move echoes broader trends across Africa. Countries like Tanzania, Ghana, and Mali have all revised mining agreements in recent years to claim greater state participation. The pattern reflects a new resource nationalism. One that seeks to balance investor returns with citizens’ demands for fairer distribution of wealth.

If managed well, Burkina Faso could position itself as a model for recalibrating extractive industries in fragile states. If mismanaged, however, the reforms risk alienating investors without delivering on promises to the people.

The updated mining code is only the first step. The real test lies ahead: will the additional 5% government stake be channeled into visible improvements for citizens, or will it vanish into the machinery of war and bureaucracy?

For now, Burkina Faso has secured a bigger slice of the gold pie. Whether that slice nourishes its people, strengthens its democracy and supports lasting peace is a question the country and its leaders must urgently answer.