Ethiopia and Somaliland Maritime Agreement Collapse: Strategic Vision, Political Hesitation, Human Stakes

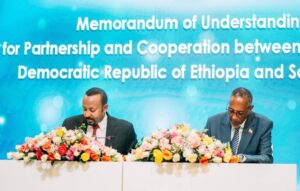

The January 2024 Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) between Ethiopia and Somaliland was more than a diplomatic announcement. It was a bold gamble, promising to reshape the Horn of Africa’s strategic landscape and redefine the futures of millions of people living in one of the world’s most fragile regions. Ethiopia saw in the MoU a long-awaited chance to solve the maritime vulnerability that has haunted its policy establishment since 1993. Somaliland saw a path to long-denied political legitimacy and economic uplift. To the ordinary citizens, the agreement implied new trade opportunities, jobs, regional stability, etc. Conversely, its collapse exposed the widening gap between strategic ambition and political execution in Addis Ababa, illuminating the emerging global reality that functional governance increasingly matters as much as traditional state recognition.

More than thirty years after becoming landlocked following Eritrea’s independence in 1993, Ethiopia, Africa’s second most populous country, remains without direct access to the sea. While landmark projects like the Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam (GERD) have brought energy security, the absence of a coastline continues to constrain Ethiopia’s economic potential and strategic autonomy. Overtime, the topic of sea access was politically sensitive and largely avoided in public discourse. However, that has changed. The Prime Minister of Ethiopia, Abiy Ahmed, has placed the issue back at the forefront, reframing Ethiopia’s lack of maritime access not simply as a historical consequence, but as a pressing developmental and geopolitical challenge.

![]()

With a population exceeding 126 million and projected to surpass 150 million by 2030 (World Bank, 2024), Ethiopia argues that remaining in what officials describe as a “geographic prison” is no longer sustainable. This claim is rooted not only in demographic pressures, but also in Ethiopia’s long maritime history and increasing vulnerability due to dependence on a single foreign port.

The Horn of Africa’s political terrain is notoriously complex. A dense web of colonial cartography, post-independence conflicts and great-power rivalries. In this volatile environment, Addis Ababa’s quest for maritime access has been more than necessary. Ethiopia’s dependence on Djibouti, where roughly 95% of its imports and exports move, has become a national anxiety, raising transportation costs, limiting economic diversification and magnifying political risk.

On the Somaliland’s phase, history tells a different story but reveals an equally compelling urgency. Re-emerging from the ashes of Somalia’s 1991 collapse, it built democratic institutions, maintained internal peace and nurtured functioning security forces, with a rare achievement in the region. But without international recognition, economic expansion remained throttled, foreign investment restricted and its youth often forced into migration as the only path to prosperity.

The MoU offered a convergence of needs. Ethiopia would gain alternative port access through Berbera; Somaliland would gain the political acknowledgment it has sought for in decades. Millions stood to benefit from new infrastructure, new trade routes and new cross-border economic activity.

Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed’s two-water policy, which are the doctrinal framework behind the MoU, reflected a modern understanding of geopolitics. In a global economy defined by supply-chain rivalry and chokepoint politics, Ethiopia’s inability to secure maritime leverage weakened both its economic future and diplomatic influence. And Berbera presented a rare solution. A deep-water port backed by major Gulf investment and positioned at the doorstep of the Bab el-Mandeb strait, a maritime artery linking Europe and Asia.

But Ethiopia’s leadership misjudged both the region’s political sensitivities and the international repercussions. Somalia denounced the MoU as an existential threat. The African Union invoked its long-standing policy against altering colonial borders. The Arab League mobilized diplomatic pressure. Ethiopia, instead of defending its initiative, retreated, insisting the agreement was merely technical rather than political.

This hesitation stalled potential job creation in eastern Ethiopia and Somaliland, undermined private investors’ venturing and painted an odd picture to international partners that Ethiopia lacked coherence in its strategic planning.

The MoU’s collapse cannot be explained by diplomacy alone. Ethiopia’s domestic landscape has become increasingly fragmented; overlapping centers of power, competing regional interests, and economic pressures that limit the government’s ability to invest in major infrastructure projects. A state that once projected confidence across Africa now struggles to harmonize internal priorities, making ambitious foreign initiatives difficult to sustain. This disjointment has international implications. Ethiopia’s retreat opened diplomatic space for other actors such as Western governments, Gulf States and Asian powers, to solidify their engagement with Somaliland. Suddenly, recognition of Somaliland, which was once a diplomatic taboo, has lately become a topic of serious conversation in Washington, London, Abu Dhabi and Brussels.

Amid these geopolitical maneuvers, some of the affected sociocultural dimensions cover the To the Ethiopian traders and transport workers – access to a second port could have reduced shipping costs, stimulated local markets, and eased inflationary pressures. To the Somaliland’s youth – recognition or even quasi-recognition could unlock international investment, reducing unemployment and giving families alternatives to dangerous migration routes. To the pastoral communities across the Ethiopia-Somaliland border – improved infrastructure and freer movement of goods could have strengthened livelihoods long battered by climate shocks and insecurity. To the wider region – a functional economic corridor between Addis Ababa and Berbera could have become a stabilizing force, reducing incentives for armed conflict and enabling more predictable cross-border cooperation.

The collapse of the MoU is therefore not just a diplomatic failure, but a missed opportunity for human development in one of the world’s most underserved regions.

Further than bilateral relations, the episode has accelerated a significant transition; the decline of Ethiopia’s hegemonic role in the Horn of Africa. Once the region’s anchor state, Ethiopia increasingly competes with assertive neighbors and well-funded Gulf rivals. Djibouti now seeks to solidify its dominance as Ethiopia’s lifeline. Eritrea sees leverage in Ethiopia’s maritime desperation. Kenya and Uganda are engaging Somaliland more openly, valuing practicality over orthodox politics.

Meanwhile, global powers like China, US, Russia, UAE are viewing the Red Sea as an emerging arena of strategic contest. A stable, democratic Somaliland fits neatly into many of these big actors’ calculations, highlighting how performance-based relevance can reshape notions of sovereignty.

The Ethiopia-Somaliland MoU may have collapsed, but its political, economic and human implications continue to reverberate. It exposed Ethiopia’s urgent need to rebuild institutional coherence, economic resilience and diplomatic credibility. It painted Somaliland’s growing international appeal as a functionally stable political entity. And it revealed a fluid continental order in which governance performance increasingly speaks louder than inherited borders. Most of all, it demonstrated that in the Horn of Africa, hesitation strategic advancement is a political misstep and missed chance to improve sociocultural economy for a stable future.

The next chapter in this story will be written not only by states and diplomats, but by the millions whose aspirations for economic security, depend on decisions taken in Addis Ababa, Hargeisa, and beyond.