Ethiopia’s Living Heritage in the Holy Land: History, Faith and an Enduring Presence

Roughly 95 kilometers from Nazareth, the mountain ridges open like unfurled wings above cultivated plains, guiding travelers toward a city built around one of Christianity’s most cherished sites – the Basilica of the Annunciation. Here, tradition holds that the Virgin Mary first learned she would bear a son, and the quiet hum of devotion remains woven into the modern landscape.

Inside the basilica’s gated compound, history rises in visible layers. Beneath the soaring 20th-century structure lie the remains of Crusader chapels, Byzantine walls and Roman stone foundations. At its heart sits the Grotto of the Annunciation, long revered as the home of Mary. Above it, mosaics from Christian communities worldwide shimmer in the sanctuary’s light.

![]()

Pilgrims like Carlos Velez of Puerto Rico come seeking a direct encounter with the past. He sees in the Basilica not just religious significance but a testament to changing attitudes toward heritage. “The beauty of 20th-century archaeology”, he said, “is that people understood the importance of preserving the old—letting visitors see time itself instead of simplifying it into one style”. To him, the site embodies both faith and the delicate politics of memory.

Jerusalem, a city of devotion and disputes. South of Nazareth, Jerusalem rises as the spiritual axis for billions. A city dense with sacred geography and geopolitical complexity. Its Old City enclosed by the 16th-century walls of Sultan Suleyman, remains a labyrinth of shrines, markets and centuries-old tensions. Among these tensions sits one of the most enduring Ethiopian presences in the Holy Land.

![]()

![]()

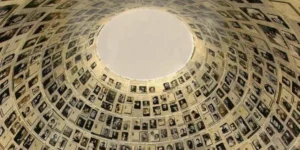

Each year, tens of thousands of Ethiopian Jews gather on the 29th of Heshvan to celebrate Sigd, a festival of renewal rooted in Ethiopia’s ancient Beta Israel traditions. At the Armon Hanatziv Promenade overlooking the Temple Mount, participants fast, pray and listen to Kessim reading from the Orit, their Ge’ez scripture. What began as a uniquely Ethiopian ritual has, since its official recognition in 2008, grown into a national event in Israel, symbolizing both cultural pride and the ongoing struggle for full social inclusion.

Betelhem, an Ethiopian-born Israeli, sees Sigd’s rising national profile as a step toward greater visibility for her community. She said “during Sigd we renew our covenant. But we also renew our call for recognition. Our story is part of Jerusalem’s story”. Her words reflect both celebration and the social realities Ethiopian Jews continue to navigate, embedding questions of integration, identity and belonging within Israeli politics.

![]()

A sacred presence under pressure. Away from the Jewish Quarter, Ethiopia’s Christian heritage stands firmly, though sometimes precariously within Jerusalem’s Christian Quarter. Right there, within the compounds linked to the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus, Ethiopian monks maintain a centuries-old tradition of guardianship. But their presence is also marked by dispute.

Abba Gebereselassi Tesfa, who has served for 35 years, speaks of deep-rooted tensions over ecclesiastical property. In his words – “they stole what is ours,” he said, referring to longstanding conflicts with Egyptian clergy over control of Ethiopian sacred spaces. These conflicts, shaped by shifting empires and religious politics, highlight how spiritual sites in Jerusalem are inseparable from diplomatic realities.

![]()

He also voices a quieter struggle of daily life. The monks’ living quarters are aging, and resources are thin. He urges the Ethiopian government to do more. “We cannot serve properly while living below standards”, he said. His plea underlines a larger political question of how does a modern state safeguard its heritage abroad, especially when that heritage rests inside one of the world’s most contested cities?

However, many visitors encounter these spaces primarily as havens of peace. Alemtsehay Belete, who moved from Ethiopia’s Tigray region over two decades ago, returns often for solace. “I feel complete whenever I come here”, she said. To her, the Ethiopian monastery is not a political battleground but a spiritual anchor that connects her past and present.

Ethiopian street is a quiet corridor of history. Just beyond the Old City walls, Ethiopian Street leads to the Kidane Mehret Church and the Debre Genet monastery, founded on land purchased in the late 19th century under Emperor Yohannes IV with support from Emperor Menelik II. The church’s circular structure like three concentric rings surrounding the sanctuary, shows distinct Ethiopian liturgical traditions, preserved intact amid Jerusalem’s diverse Christian heritage. The monastery remains home to clergy, nuns and lay residents. Its operations is supported partly through nearby rented properties. These compounds serve as cultural and historical bridges, grounding Ethiopians in a city where identity, faith and territory have always been intertwined.

A heritage that endures. Across Nazareth and Jerusalem, Ethiopia’s spiritual footprint is more than a historical curiosity. It is a living testament to centuries of devotion, migration, strength, etc. These spaces illuminate the Ethiopia’s ancient ties to the Holy Land and the ongoing social/political negotiations that shape communities today.

In a region where every stone carries memory, Ethiopia’s heritage stands as a reminder that sacred history is not static. It is lived daily by the people who preserve it, revere it and continue to seek their place within the complex mosaic of the Holy Land.