Nations of Paradox: Countries in the World, where Fuel Flows Cheaper than Water

In most parts of the world, water is life and fuel is luxury. Yet, in a curious twist of economics and geography, there are nations where the price of a liter of gasoline undercuts that of bottled water. These are countries blessed (or burdened) with vast oil wealth, compound subsidy systems, and environmental contrasts that turn basic needs into symbols of inequality.

From the deserts of Saudi Arabia to the streets of Caracas, the cost of keeping a car running can be less than keeping a family hydrated. Here’s a closer look at six nations where fuel flow sells cheaper than water and what that reveals about the intersection of politics, resources, and daily life.

![]()

Libya – oil rich, water poor: In Libya, a liter of gasoline costs around $0.03, while bottled water goes for about $0.45. The numbers are staggering, but they tell a great story. Libya sits atop some of the world’s richest oil fields, and for decades, state subsidies have made fuel almost free. But water is another story. The North African nation’s arid climate and fragile infrastructure make clean water a costly commodity. As it is said by some residents in Tripoli –“You can fill your car easily, but not always your glass.”

Venezuela – a crisis of contradictions: In Venezuela petrol prices hover near $0.02 per liter, one of the lowest globally. Thanks to heavy government subsidies and a national identity built around oil. But then, the same policies that make driving cheap have helped push the economy into disarray. Bottled water costs about $0.60 per liter, reflecting shortages, inflation and a crumbling public supply. Venezuelan families see water as luxurious item, compared to fuel.

Saudi Arabia – the desert’s duality: In Saudi Arabia, fuel costs roughly $0.58 per liter, while bottled water can exceed $1.20. Here, oil wealth has long powered both economic might and cheap energy. Yet, the Kingdom’s geography with vast arid desert, makes fresh water one of its scarcest resources. Desalination plants line the coast, turning seawater into something drinkable at a high environmental and financial cost. Even as the government invests in sustainability, the irony persists: fuel remains plentiful, water precious.

Kuwait – the price of luxury: While bottled water costs around $1.50, citizens pay about $0.34 per liter for fuel in Kuwait. Oil wealth has turned this tiny Gulf state into one of the world’s richest countries, yet its environment yields almost no natural freshwater. Every drop of drinkable water is desalinated and transported. A process more expensive than pumping crude from the ground. In Kuwait’s supermarkets, the price tags tell the story of a desert kingdom where wealth cannot buy geography.

Angola – subsidized survival: In Angola, gasoline sells for $0.33 per liter, while bottled water averages $0.80. The government’s fuel subsidies are a holdover from its oil boom years, meant to ease economic hardship. But water distribution remains fragmented and unreliable, especially outside Luanda. With regards to most rural families, fetching water can take hours, which makes it far more expensive in labor than fuel ever could be in Angola.

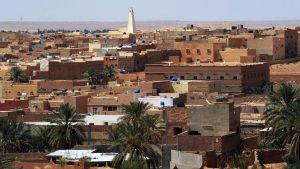

Algeria – the uneven balance: In Algeria, motorists pay around $0.34 per liter for petrol, while bottled water costs roughly $0.50. The nation’s heavy reliance on oil exports allows for low fuel prices, yet water infrastructure lags behind. With rising urban demand and erratic rainfall, even modest water costs reflect a growing scarcity issue.

These nations are parts of a tongue-in-cheek world of economic imbalances: that fuel purchase at filling stations across these locations, can be cheaper than drinking water, or a unit of water bottle, highlights a contradiction at the heart of global economics. This is a story of abundant resource clashing with environmental reality of human need, in nations where the ground gives free oil wealth and withholds life essential – water.

This socioeconomic imbalance shapes daily life for families in these countries. A state of cheap mobility, yet expensive survival. One’s rhetoric question would be to ask – how long can a world so thirsty for both energy and water afford to keep a management disparity of the essential commodities, regardless?