Sahel Nations: Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger Move to Exit ICC and Create Sahelian Criminal Court for Human Rights – a regional court

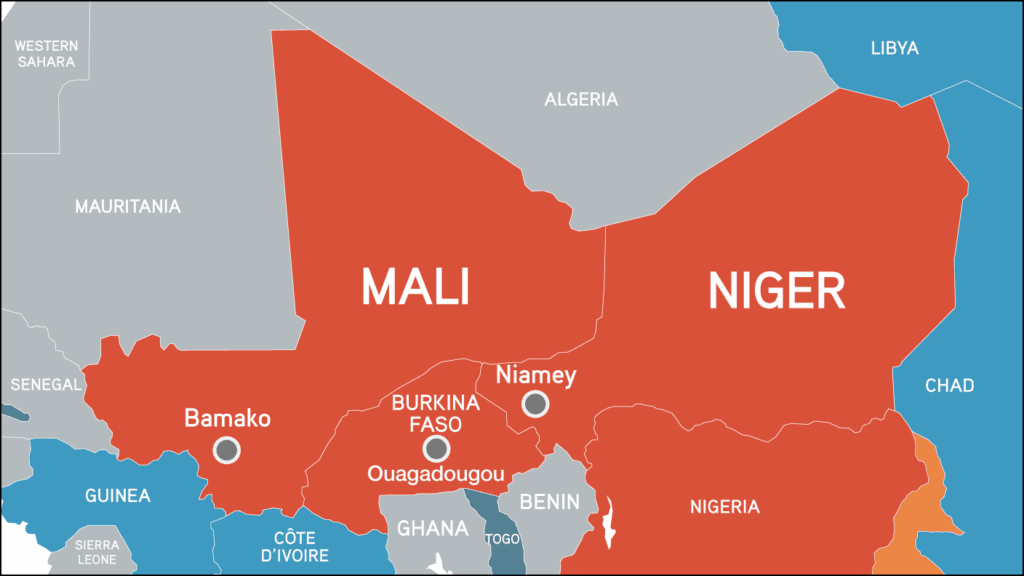

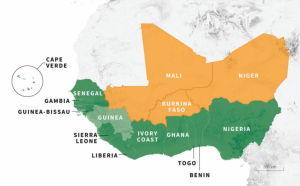

The Sahel region’s shifting political landscape took another dramatic turn, as the justice ministers of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger convened in Niamey to finalise a joint plan to withdraw from the International Criminal Court (ICC) and establish their own judicial body – the Sahelian Criminal Court for Human Rights. The move agreed upon during an extraordinary summit of the Confederation of Sahel States (CSS) on September 16, marks a historic breakoff from the Hague-based tribunal, and underscores the region’s attempt to redefine its sovereignty and governance approach to justice amid ongoing crises of conflict, displacement and political transition.

Breaking away from the Hague, which has held international legal jurisdiction over African leaders for decades or individuals, or rebel leaders, has ushered decolonisational-construct. African leaders have voiced unease over the ICC accusing them of disproportionately targeting the continent while neglecting abuses elsewhere. The CSS’s latest step crystallizes that criticism into political action.

Being forthright in his rebuke, the Niger’s acting Prime Minister, General Mohamed Toumba said: “The time has come to reconsider participation in the Rome Statute. The ICC has functioned less as an impartial arbiter of justice and more as an instrument of repression against African countries.”

Toumba charged that prosecutions often proceeded on false grounds of serious and widespread human rights violations. This opinion echoes the long-standing African Union complaints that the ICC undermines the reinforcement of national and regional judicial systems.

According to diplomatic sources in Niamey, the legal paperwork required for the withdrawal has already been drafted. A formal declaration is expected within days, paving the way for the operationalisation of the Sahelian Criminal Court for Human Rights. A regional court to address the insurgent and rebellious leadership against security and other sundry political issues that trouble the region, or may arise in future.

The proposed Sahelian court would be tasked with investigating crimes against humanity, war crimes, terrorism, genocide and other violations. Issues that have scarred the Sahel for decades, or may arise in future. Mali’s north remains plagued by jihadist insurgencies; Burkina Faso continues to face attacks that have displaced more people; Niger also grapples with both militant violence and political instability even as restructuring is processing in.

In some closest, some leaders believe that an established legal community of a regional tribunal, rooted in Sahelian realities, will be better equipped to deliver justice that resonates with the local communities and traditions. Unlike the ICC, which has struggled to prosecute cases effectively and is often seen as distant, the Sahelian Regional Court could combine African customary justice with modern legal frameworks. This is not just about legal sovereignty, but about humanity. Families are torn apart, people have been displaced by violence and rebellious insensitive warlords. Thus, a need of a legal institution that swiftly and justly speaks to address the suffering of Africans is inevitable; not depending on one that lectures from afar without understanding the sociocultural fabrics that weaves together the existence of the Africans in Africa. Taking back the strategy of enchanting political power.

The withdrawal is also deeply political. Since the entrance of this recent junta in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, the regimes have increasingly distanced themselves from Western powers and sought closer ties with Russia and regional blocs. The exit from the ICC, an institution often backed by European governments, represents another step in their effort to reassert independence on the global stage.

However, there is a mix of critics questioning the credibility of creating a new court, and asking if sociocultural accountability of justice would be dished without manipulation from the very governments that have been accused of all sorts from political-lefties across the world. Will the Sahelian court truly protect victims based on human right standardisation? Or will it become another tool of political survival for ruling juntas? In another view, the CSS strategy may not merely be judicial but symbolic. And mostlikely, it signals a way of projecting unity in a region fragmented by insecurity. Creating a shared court, the Sahel states are motioning both defiance to external pressure and solidarity among themselves.

In view of the history of justice and betrayal, Africa’s relationship with the ICC has always been fraught. While African nations were among the first to sign the Rome Statute, they have since grown disillusioned, accusing the court of double standards. Nearly all of the ICC’s high-profile prosecutions have targeted Africans. From Sudan’s Omar Al-Bashir to Kenya’s Uhuru Kenyatta; fueling accusations of selective justice. Yet the ICC has also been a court of last resort for victims when national systems fail. In war-torn regions like Darfur and the Democratic Republic of Congo, it provided a global platform to highlight atrocities. The Sahel’s move to abandon it, risks leaving vulnerable communities without that safety net. Unless, the new Sahelian court can truly deliver.

From the human dimension to beyond the politics and legalese, lies the implicative cost to humanity. Some villages in Mali and Burkina Faso have been wiped out by extremist violence. Families are fractured, with women and children bearing the brunt of displacement and trauma. Communities in Niger continue to face both armed conflict and the humanitarian toll of sanctions imposed after last year’s coup.

Most African survivors see the promise of justice, whether through the ICC or any other regional court as an unfelt-distant nonconcrete justice, bounded up in the lecture of hope of accountability, reconciliation and rebuilding fractured societies. Aïcha, a displaced mother from central Mali now living in Niamey said –“The wars we lived through are not numbers on a report. If they build this court, let it not be for politicians, let it be for us the people who have suffered.”

The road ahead for the Sahelian Criminal Court for Human Rights is uncertain, though visionary and decisive. Establishing legitimacy, securing funding and defining its jurisdiction will be monumental commitments. The court will need to convince both its citizens and the broader international community that it can deliver credibly independent justice.

Conversely, what is clear is that Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger are carving out a new path for other African countries toll. One that blends politically definitive leadership with regional solidarity; and one that will test whether Africa can design institutions that reflect both its struggles and its aspirations, in subtly self-decolonisation.

The stakes could not be higher for the Sahel region that has been haunted by wars, genocide and fractured families.