Somalia, Regional States Move toward Joint Control of Oil and Minerals Amid Political Fault Lines

Mogadishu (HOL) – Somalia’s federal government and four regional administrations have agreed to deepen cooperation and jointly manage the country’s petroleum and mineral resources, a move officials say could help ease long-running political tensions over control of a sector widely seen as central to the nation’s economic future.

The agreement was announced Monday at the end of a three-day conference in Mogadishu bringing together the Ministry of Petroleum and Mineral Resources and its state-level counterparts. Federal Petroleum Minister Dahir Shire Mohamed framed the talks as an attempt to replace rivalry with coordination in a sector that has historically fueled mistrust between Mogadishu and the regions.

“We have once again agreed to reject division and take coordinated measures to ensure that petroleum and mineral resources are developed jointly,” Dahir told reporters, stressing that decisions would be guided by the “shared interests of the Somali people.”

Behind the formal language lies a deeper challenge: how to turn Somalia’s natural wealth into broad-based benefits without repeating past patterns in which resources became drivers of conflict rather than development. For many Somali families, the promise of oil and minerals is tied to hopes for jobs, better services, and relief from decades of poverty and displacement. At the same time, there is widespread concern that poor governance could allow revenues to bypass ordinary citizens and concentrate power and wealth in the hands of a few.

Officials said the conference focused on aligning federal and state institutions around existing national laws and regulations, while respecting constitutional provisions that grant regions a role in resource management. Participants also discussed protecting sensitive geological data, improving security around exploration sites, and expanding technical training so Somalis, not just foreign contractors can work in the sector.

“These resources belong to the public,” one conference participant said privately. “If communities do not see tangible benefits, the legitimacy of any agreement will be questioned.”

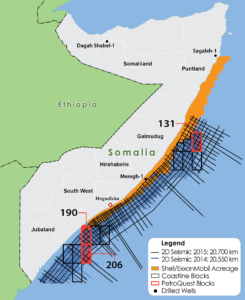

The business stakes are rising. Somalia’s offshore basins are considered underexplored but potentially significant, attracting renewed international interest. Days before the conference, Turkey’s energy minister, Alparslan Bayraktar, announced plans to deploy a drilling vessel to Somali waters in February for Ankara’s first deepwater energy exploration project abroad. The operation, involving the Cagri Bey drilling ship, signals growing confidence among foreign partners but also heightens the need for clear, unified governance to manage contracts, revenues, and environmental risks.

Politically, the absence of Puntland and Jubbaland from the Mogadishu meeting underscored unresolved disputes between those states and the federal government. Their boycott reflects broader disagreements over power-sharing and constitutional interpretation, raising questions about whether a national consensus on resource management is truly within reach.

Analysts say the agreement is nonetheless a modest step toward rebuilding trust. “Even partial alignment can reduce uncertainty for investors and set norms for cooperation,” said one Somali governance expert. “But the real test will be implementation—especially transparency, revenue sharing, and community consultation.”

![]()

Somalia has long viewed oil and gas as a potential engine for recovery after decades of conflict. Yet insecurity, political fragmentation, and the lack of a fully settled resource-sharing framework have slowed progress. As exploration activity accelerates, the challenge for Somali leaders will be to ensure that natural resources become a unifying asset, strengthening institutions, supporting families and local economies; and reinforcing social cohesion, rather than another fault line in an already fragile political landscape.