Tanzania’s Vanishing Soils, How Erosion is Stripping the Nation’s Fertile Heartland

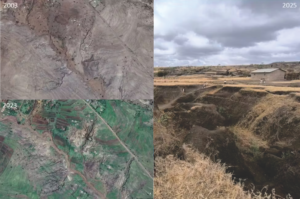

On the slopes of northern Tanzania, extensive trenches slice through fields that once grew maize, beans, vegetables, etc. In some villages, these gullies are wide enough to swallow footpaths, fences and sections of road. Farmers and pastoralists who depend on the land, see that the soil erosion is no longer an abstract environmental concern, than a daily threat to food, income and sociosecurity.

Gully erosion happens when flowing rainwater cuts rapidly into the ground and it is spreading across large parts of the Tanzanian highlands. What was once a slow natural process, has accelerated into a crisis with human, economic and political consequences. Researchers now warn that soil loss is undermining national development goals, pushing already vulnerable communities closer to hunger/displacement, driving a transit from environmental process to humanitarian risk.

Erosion happens everywhere. Rain breaks soil into particles, which are then carried downhill into rivers and lakes. But in Tanzania, erosion rates have increased dramatically over the past century. Scientists estimated that soil is being lost around 20 times faster than it was 120 years ago, and more than half of the country’s land area shows signs of rapid degradation. The reasons are partly natural.

Northern Tanzania’s steep landscapes, erratic rainfall and fragile volcanic soils make the region inherently vulnerable. These soils that formed from ancient basalt as the East African Rift opened, are rich but unstable. After long dry periods, intense rain can cause them to disperse into fine particles that wash away easily. Moreso, the way lands are now used, has turned vulnerability into crisis.

Clearing forests and savannahs for farming, combined with rising livestock numbers, has stripped soils of the vegetation and roots that was holding them together. When heavy rain arrives, water rushes downslope concentrating in valleys and tearing open gullies that grow larger each season. A farmer near Arusha told researchers that “these are not just cracks in the earth. They are eating our farms”.

Indigenous land management systems once reduced these risks. Seasonal grazing, fallowing/shifting cultivation allowed vegetation to recover, while soils rebuild. But these practices were steadily diluted during colonial rule and after independence, as policies favoured permanent settlement, fixed land boundaries and continuous cultivation.

Pastoralist groups such as the Maasai were pushed into smaller areas and encouraged or forced to abandon seasonal movement of livestock. Over time, grazing pressure intensified. Livestock densities tripled in some regions over the past 50 years, leaving land permanently exposed.

At the same time, Tanzania’s population has doubled roughly every 25 years, exceeding 70 million persons. With more mouths to feed, families farm steeper slopes and cultivate land that was once left to recover. And as for many households, there is simply no alternative. The result is a landscape pushed past a tipping point. Once gullies form in these volcanic soils, they are extremely hard to stop. Even if grazing pressure is reduced or trees are replanted, the channels continue to extend, draining water, nutrients and seeds from surrounding land.

![]()

The loss of soil translates directly into lost livelihoods. Around 70% of Tanzanians are smallholder farmers who produce most of the country’s food. As erosion reduces yields, food insecurity spreads. Already, more than half of the population experiences moderate to severe food insecurity. Infrastructure also suffers. Field surveys show that gullies damaging roads and bridges within a decade of construction. In the rural communities, these situations mean isolation from markets, schools and health services. Farmers report that they are being forced to grow low-value crops for survival rather than higher-value produce that requires reliable transport.

The environmental damage extends far beyond farms. Sediment washed from eroding hillsides fills rivers, reservoirs and lakes. In Lake Manyara National Park, a UNESCO Man and Biosphere Reserve researchers have documented rapid sedimentation threatening fisheries, tourism, wildlife habitats, etc. that support elephants, lions and more than 350 bird species. These losses carry national economic costs, yet they often remain invisible in policy debates and short-term growth strategic sessions.

Despite the scale of the problem, erosion is not inevitable. Across East Africa, communities have long used techniques that work with natural processes, such as earth bunds and terraces to slow water, the replanting of grasses/trees to stabilise soil and so on. Programmes such as Jali Ardhi (“Care for the Land”), a collaboration between Tanzanian communities and international researchers, are combining scientific monitoring with citizen science to track gully growth and test restoration methods. NGOs including the LEAD Foundation and Justdiggit are supporting village-led efforts to revive and adapt traditional practices. In some areas, collective action has successfully stabilised small gullies and improved soil fertility. The benefits are immediate better yields, reduced flood damage and reassuring that land can recover.

But many of the largest gullies, featuring some with tens of metres wide and several kilometres long, are beyond the capacity of resourceless-poor communities to fix alone. Restoration at this scale requires machinery, technical expertise and sustained funding, beckoning on governance prioritization for developmental repairs.

Tanzania has committed internationally to the UN Convention to Combat Desertification and its Land Degradation Neutrality targets. On paper, this indicates a recognition of the problem. In practice, long-term investment plans remain limited and local authorities often lack the resources to act. There is also a mismatch between national political cycles and the slow, patient work of land restoration. Benefits may take years to materialise, while costs are immediate. This is a systemic-structural challenge where short-term visibility often drives decision-making.

Experts argue that treating erosion as a purely environmental issue misses the point. Soil loss is tied to poverty, land tenure insecurity, education, corruption and uneven development. Addressing it requires coordinated policies that support, pastoralists, strengthening local governance and value indigenous knowledge, alongside scientific research.

More than half of Tanzanians are under 18, growing up on land already under strain. Whether that land can continue to feed and support them is a political question, as much as an environmental one. If action is delayed, the gullies will keep growing with the youth, which could paint socioeconomic cracks in the country’s future.