Trump’s ‘Donroe Doctrine’ Inspired by a 200Years Old Foreign Policy: What It Means on the Ground

When President Donald Trump described the U.S. operation that led to the removal of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro, he framed it as more than a single foreign-policy decision. He said it was the revival and reinvention of a 200 years old idea. Standing before reporters at his Mar-a-Lago resort, Trump announced what he called the “Donroe Doctrine,” a pointed rebranding of the Monroe Doctrine that has shaped US relations with the Western Hemisphere since 1823.

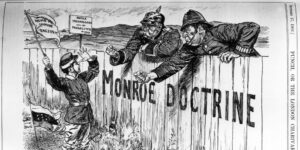

The original Monroe Doctrine, introduced by President James Monroe, warned European powers against colonizing or interfering in the Americas. Trump argues that his administration is restoring that principle for a new era. Which is sparked by rival powers according, illicit networks and strategic competition close to US borders, according to him.

“Under Maduro, Venezuela welcomed foreign adversaries into our region” Trump said, alleging the presence of hostile actors and weapons systems that posed a threat to U.S. lives and interests. Such actions, he argued, violated “the core principles of American foreign policy” stretching back more than two centuries. “We’ve superseded it by a lot,” he added. “They now call it the – Donroe Doctrine”. The White House’s message was quickly reinforced by the State Department, with a post on X: “This is OUR Hemisphere, and President Trump will not allow our security to be threatened”.

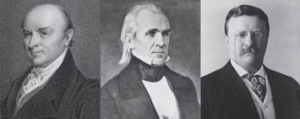

Trump’s invocation of the Monroe Doctrine is not new. A portrait of James Monroe hangs near the president’s desk in the Oval Office, and references to the doctrine have appeared repeatedly in Trump-era speeches and strategy documents. On the doctrine’s anniversary last December, Trump praised Monroe’s “bold policy” and announced a new “Trump Corollary,” later detailed in a national security strategy focused heavily on the Western Hemisphere.

What distinguishes this moment, analysts say, is the administration’s willingness to pair historical language with direct action, and to present those actions as both protective and transformative.

![]()

Supporters within the administration argue the approach advances US security while opening space for democratic transitions and economic recovery in countries long plagued by corruption and repression. In Venezuela, officials have emphasized humanitarian goals, pointing to years of shortages, mass migration, and political crackdowns. “The goal is stability and a safe, orderly transition”, Marco Rubio – Secretary of State said, stressing that Washington intends to use economic leverage rather than direct governance.

However, critics are warning that the language of doctrine can obscure the realities of intervention. As for many in Latin America, the Monroe Doctrine is remembered less as a shield against imperialism and more as a justification for it. The long shadow of 1823 policy.

![]()

Monroe first outlined his doctrine in a routine annual message to Congress, declaring that the Americas were no longer open to European colonization. Over time, that statement evolved into a flexible tool of US power.

In 1865, the US backed Mexican forces against a French-installed emperor. At the end of the 19th century, it went to war with Spain, emerging with new territories and deep influence over Cuba. President Theodore Roosevelt later expanded the doctrine with his own corollary, asserting the U.S. right to act as an “international police power” in cases of “chronic wrongdoing.”

That expansion led to repeated US military interventions across the Caribbean and Central America. During the Cold War, the doctrine’s logic merged with anti-communist strategy, shaping US involvement in coups, covert operations and confrontations, from Guatemala and Chile to Cuba’s missile crisis.

Eduardo Gamarra, a professor of international relations at Florida International University, has described this approach as one of strategic denial keeping rival powers out of the region. “In the 1800s, that meant Europeans. In the 20th century, it meant the Soviet Union”, he said.

![]()

By the early 2010s, US officials appeared ready to move on. In 2013, then Secretary of State John Kerry, declared the Monroe Doctrine era is over, calling instead for partnerships based on equality and shared responsibility. Which was a shift from rhetoric to action.

Trump’s return to office has marked a sharp departure from that vision. While his first term emphasized “America First” and skepticism of overseas entanglements, his second has featured a more assertive posture.

Even before taking office again, Trump floated the idea of acquiring Greenland and regaining control of the Panama Canal, refusing to rule out force. His administration later authorized strikes on Iranian nuclear facilities and steadily escalated pressure on Venezuela, through sanctions, maritime interdictions and military deployments, before the operation that led to Maduro’s capture.

Trump has since suggested further interventions, including in Colombia and Mexico, and warned that the US could act if Iranian authorities violently suppress protesters. Each statement reinforces the administration’s claim that the United States is reclaiming control over its strategic neighborhood.

The national security strategy underpinning this approach is explicit: it seeks to block “non-Hemispheric competitors” from controlling key assets or positioning forces in the Americas. It also signals a tougher stance toward European allies, accusing them of strategic drift and calling for resistance to Europe’s current political trajectory.

Farther than the doctrine and strategy, the consequences are deeply human. In Venezuela, families fractured by migration are watching closely to see whether political change brings relief or renewed instability. Regional leaders, meanwhile, are weighing how a more interventionist U.S. affects their own sovereignty and domestic politics.

Grassroots organizations across Latin America have voiced mixed reactions. Some activists welcome pressure on authoritarian governments; others fear a return to a past where external decisions shaped local futures with little accountability.

![]()

John Bolton, Trump’s former national security adviser, has been blunt in his assessment. “There is no Trump Doctrine,” he said recently. “There’s no grand conceptual framework. It’s whatever suits him at the moment”.

Whether the “Donroe Doctrine” becomes a lasting pillar of U.S. foreign policy or a momentary slogan may depend less on history than on outcomes: whether it delivers stability, respects regional voices, and improves daily life for people across the hemisphere. Two centuries after Monroe’s warning, the debate over who decides the Americas’ future is far from settled.